RELATED TERMS: Artifactuality and Actuvirtuality; Design of Narrative Environments; Narrative Environments

The following entry brings to attention a number of key themes for the design of narrative environments. They include: storytelling; social imaginaries; immersion; spatial narrative; experience design; illusion of authenticity; agency; identity; community; persistent community; participation; to live; to visit; guest; citizen; stranger; polity; synthetic and predesigned worlds; player-created and emergent worlds; interaction and narration; productive play.

A speculative chronology Part 1: From Lascaux to Disneyland

Celia Pearce (1997a: 329) uses the term ‘narrative environments’ to describe physical or virtual spaces that tell a story or provide an experience for particular audiences. She says that a narrative environment, simply put, is a space that facilitates a story. In her view, the first commercial attempts to create narrative environments as an entertainment form were developed by Walt Disney for Disneyland. Disney fused architecture and cinema and, for the first time, made environments that told a story.

Centuries before Disney created narrative environments for entertainment purposes, Pearce (1997a: 330-331) continues, they existed for religious and educational purposes. In the pre-literate days of medieval Roman Catholicism, for example, when the mass was recited in Latin, understood only by priests, monks and noblemen, the Biblical stories were articulated for the illiterate peasants through frescos, murals, statues, reliefs and stained-glass windows, in short, by pictorial-sculptural means in an architectural setting. The church interior, from this perspective, can be argued to constitute a narrative environment of a sort, articulating visual, pictorial narratives in space while working image into architecture.

Still further back historically, Pearce argues that more examples of the articulation of image and architecture can be found. She cites Ancient Egypt, where giant frescos were the preferred medium, and Mesopotamia, where visual narratives kept alive the lore, legend, history and myth of these civilisations. Yet further back historically, Pearce speculates that the cave paintings of Lascaux may be read as attempts to embed a chronicle of events within the cave dwellers’ environment, perhaps with pedagogic intent, conveying instructions concerning how to hunt certain animals.

In sum, architectures, as environments, have functioned as a narrative medium for millennia.

A speculative chronology Part 2: Disneyland as creative erasure

As already noted, in 1955 Walt Disney opened Disneyland in Anaheim, California, which many regard as the first-ever theme park. A synthesis of architecture and story, it was a revival of narrative architecture, a style that had previously been reserved for religious, ritual functions, from the royal tombs of Mesopotamia and Egypt to the temples of the Aztecs to the great cathedrals of Europe.

In contrast to such highly controlled, ritual-oriented narrative spaces, cities might be said to have rich, emergent folk narratives of their own, one which articulates messy, unplanned stories of ad-hoc expansion (Mumford 1961, Brand 1994). However, such messy actuality can be given a narrative gloss, as in the case of Los Angeles. Through the combined machinations of Hollywood and efficient real estate, Los Angeles’ short and far-from-glamorous real-life history of immigration, agriculture and boosterism was supplanted by a mise en scène of movie backdrops, a ‘social imaginary’ of the fictional histories of Los Angeles (Klein 1997). This was the sociocultural milieu, at the crest of the 20th century, in which Disneyland was born, against the backdrop of a systematically de-historicised, increasingly sprawling, automobile-enraptured Southern California.

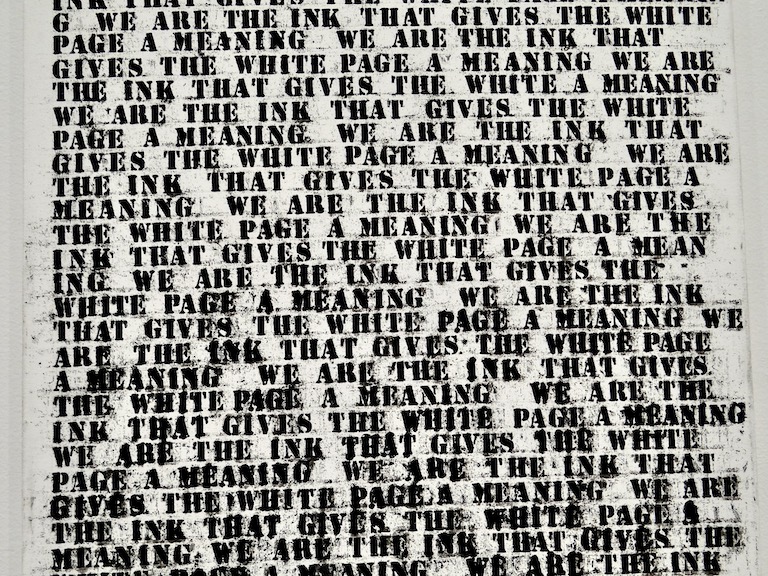

This might be taken as one key theme in the design of narrative environments: it is concerned with the creation of ‘social imaginaries’, to use Klein’s term. In other words, the design of narrative environments engages with processes of storytelling that engage with the actual, messy, multidimensional, spatio-temporal articulation of historical unfolding. It does so for some reason or purpose, perhaps to ‘demystify’ some aspects of existing dominant historiographies or, as Klein highlights, to erase memories of particular social histories and put in place a more glamorous story. This is one sense in which the design of narrative environments is engaged in ‘world building’.

To return to Pearce’s narration, she notes that rather than being a mecca for Disney animation, the vehicle for the first modern entertainment mega-brand and the prototype for transmedia, in its initial conception the theme park contained no references to Disney animation at all. It was envisioned as a kind of ‘locus populi’ of narrative space, a pedestrian haven for families, traversable only by foot or by train (Hench and Van Pelt 2003), representing a return to a more innocent past and perhaps a reaction against the suburban, freeway-interlaced sprawl that Southern California had become.

Cities like Paris, London and Athens, or even New York and Boston, are urban centres rich in history and interwoven with centuries of overlain narratives. In those contexts, there was no pressing need to create synthetic stories in the architecture. Cathedrals and castles structured the narratives of European cities. New York’s emergent stories are inscribed in the wrinkles of its weatherworn edifices. Disneyland, in contrast, was created to fill a vacuum that was uniquely regional and historical or, more accurately, ahistorical.

In some sense, Disney was trying to re-historicize Southern California. It fulfils a deep need in contemporary mass culture, particularly in the United States, for a human-scale, pedestrian experience of immersion in a three-dimensional narrative. In Europe, and even in the northeastern United States, such immersion is commonplace; in Southern California, it is not.

This last paragraph brings to attention a second key theme in the design of narrative environments: the concept of immersion. In the example above, this is represented by Disneyland bringing to Southern California a kind of immersion which is commonplace in Europe and to some extent the northeastern USA: human-scale, pedestrian experience of immersion in a three-dimensional narrative. Such immersion is not ‘total’, in the sense that attention may be broken at any point by the continuous accidental character of pedestrian experience.

A speculative chronology Part 3: Video games

Thanks in part to the advent of 3D and eventually real-time 3D in the 1990s, video games have come increasingly to resemble theme parks in terms of both design and culture. Both can be classified as ‘spatial media’ (Pearce 1997).

Digital games, with their conventions of real-time 3D and highly spatialised storytelling techniques, can be viewed as one step in the development of narrative environments with their own unique poetic structures (Klastrup 2003).

In addition to making use of the major facets of theme park creation, that is, spatial narrative, experience design, illusion of authenticity and, as already mentioned, immersion, digital games and networks also introduce three new key dimensions to spatial media: agency, identity and (persistent) community. All of these concepts are crucial for the design of narrative environments.

While spatial gaming has its precursors in text-based adventures, i.e. MUDs (Multi-User Domains) and MOOs (MUDs Object-Oriented), it began to emerge in visual form in games like the Monkey Island series (1990-2000), the landmark Myst (1993) and creative masterpieces like Blade Runner (1997) and Grim Fandango (1998). In these, the illusion of authenticity and the integration of space and story are at their highest level of artistry.

In addition to extending the player agency of the earlier spatial games through features such as added navigation, interaction with non-player characters, quest-based gameplay and dynamically interactive battle scenes, the integration of a network into MMOGs (Massively Multiplayer Online Games) creates two additional dimensions of gameplay: identity and community.

Unlike at Disneyland where every visitor is a ‘guest,’ in MMOGs, every guest is a ‘resident,’ a citizen of the online world, if you will. Following a model more akin to Renaissance fairs and live action role-playing, players are not simply spectators, but rather take the roles of elves and orcs fully engaged with the narrative and conflicts of the game. Unlike at a costume party or on Halloween, however, these identities are ‘persistent,’ meaning the player maintains the same role over time.

One game that has tried to walk the line between players having a ‘role’ and playing ‘themselves’ is the recently relaunched Myst Online: Uru Live (2003/2007). This kind of persistent identity is a prerequisite for the last and final game dimension created by digital networks: Community.

While Disneyland has generated a fan community, it does not fully realise Walt Disney’s aspiration to recapture the small town of his youth. One key reason for this is the lack of a persistent identity amongst visitors. Community arises when agency blends with persistent and recurrent attendance and an ongoing sense of participation, neither of which is afforded by the infrequent visitation scheme of theme parks.

By moving players beyond the role of spectator and towards the role of a full participant in the narrative, MMORPGs (Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Games) allow players to ‘live’ in their magical worlds as (fellow) citizens, rather than simply to visit them as guests, or strangers, once or twice a year.

This brings to attention a fourth dimension emerging in new virtual worlds such as There (2003) and Second Life (2003). In such worlds, players are not merely citizens of someone else’s fantasy world. Rather, they have a hand in constructing the fantasy themselves in what might be called ‘productive play,’ where play merges with creative production (Pearce 2006a/2006b).

For example, in There, players can design their own houses, vehicles and fashions, which then become part of the world and can be acquired by other players; while in Second Life, virtually everything in the world is created by the players.

These ‘co-constructed’ worlds merge MMOGs with user-created content such as that seen on websites like MySpace and YouTube. Yet they go beyond the scope of these latter sites by combining all player creations within a single, contiguous virtual world.

An interesting confluence of synthetic and predesigned worlds and player-created and emergent worlds, Pearce notes, is the emergence of an Uru fan culture within the player-created worlds of There and Second Life. When Uru closed in early 2004, not wishing to see their communities destroyed, players from the game migrated en masse into other virtual worlds where they began to re-create numerous cultural artefacts of their former ‘home.’ Thus, members of the ‘Uru diaspora’ in Second Life created a near-exact replica of Uru, while another group of Myst fans created a totally original Myst-style game. In There, players continue to create Uru and Myst-inspired artefacts and environments, such as a recreation of the ‘Channelwood Age,’ a game level) from the original Myst game.

A speculative chronology Part 4: Theme Parks, Cities, Massively Multiuser Online games … Theme-park-city-online-game: narrative-environment as polity

Pearce poses the question of whether MMOGs are the new theme parks or the new cities? Perhaps, she responds, in some respects, they are both. They provide the human-scale pedestrian fantasy of Disneyland, a respite from the modern, homogenous, standardised reality of automobile-based suburbia. Yet they also provide the level of ongoing participation and contribution afforded by pedestrian-friendly cities.

Furthermore, when players can contribute to the world itself, they become more like ‘theme-park-cities’ or ‘theme-park-polities’ in which players bring their own fantasies to bear on the environments.

Pearce concludes that, irrespective of whether they are highly synthetic and predesigned, like World of Warcraft, or player-created and emergent, like Second Life and There, these virtual ‘theme-park-cities’ or ‘theme-park-polities’ appear to respond to a longing that parallels Walt Disney’s initial inspiration in the mid-20th century: the desire to be part of a ‘small town,’ a community to which one can belong and, in the case of digital virtual worlds, potentially contribute creatively. In other words, a vision of a comprehensible ‘polity’, a ‘political’ vision, even if a vitally confused or paradoxical one that intermixes politics and entertainment; small scale and large scale; heterogeneity and homogeneity; and simplicity and complexity.

Narration and Interaction

Pearce (1997b) comments that, traditionally, interactive narrative has been synonymous with ‘nonlinear storytelling,’ or branching, video-based genres. Virtual reality seems to offer a more interactive alternative, which might be called ‘omnidirectional storytelling.’ However, this poses a challenge: the more interactivity, the more difficult it becomes to facilitate the story. Does relinquishing this control mean that an entirely new paradigm for story structure must be created? Can the seeming contradiction between ‘interaction’ and ‘narration’ be resolved?

References

Hench, J. and Van Pelt, P. (2003). Designing Disney: Imagineering and the Art of the Show. New York, New York. Disney Editions.

Klastrup, L. (2003) A Poetics of virtual worlds, Proceedings of the Fifth International Digital Arts and Culture Conference, pp. 100–109. Available at: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=812f7bbf5f347366591aa425dd535567b9b4c5de (Accessed: 30 December 2022).

Klein, N. M. (1997) The History of forgetting: Los Angeles and the erasure of memory. London, UK: Verso.

Pearce, C. (1997a) The Interactive book: a guide to the interactive revolution. Indianapolis, IN: Macmillan Technical Publishing.

Pearce, C. et al. (1997b) Narrative environments: Virtual reality as a storytelling medium [panel], Proceedings of the 24th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, SIGGRAPH 1997, pp. 440–441. doi: 10.1145/258734.258901.

Pearce, C. (2006a) Productive Play: Game Culture from the Bottom Up, Games and Culture, 1 (1), 17-24.

Pearce, C. (2006b) Playing ethnography: A study of emergent behaviour in online games and virtual worlds, Ph.D. Thesis, SMARTlab Centre, Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design, University of the Arts London.

Pearce, C. (2007) ‘Narrative Environments: from Disneyland to World of Warcraft’, in Borries, F. von, Walz, S. P., and Böttger, M. (eds) Space, Time, Play: Computer Games, Architecture and Urbanism: The Next Level. Basel, CH: Birkhauser, pp. 200–205. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7643-8415-9_3.

Other Resources

Celia Pearce Lecture: Virtual Reality and architecture as a narrative art (1996), SCI-Arc Media Archive