RELATED TERMS: Film making; Graphic Design; Music; Narrative environment design; Performance; Theatre; Human Actantiality; Realism; Reception theory and reader-response criticism; Epic theatre – Brecht

Audience comes from the latin audire meaning to hear. Nonetheless, it is used in film, theatre and performance to describe what might more naturally be called the spectators or viewers, as it is sight that tends to be prioritised in these media.

An audience consists of a person, more usually a group of people, who have gathered to experience a work that is presented to them. While each person has their own experience, they also share a collective experience, at a performance of theatre, music, dance or other performance formats; or the screening of a film.

It is also used as a collective noun to refer to the remote and dispersed groups who experience mass media broadcasts, such as those of television and radio.

The term can also be applied to the readership of a book, newspaper or other printed publication.

From audience to participant in the design of environments

In the context of the design practice, if the participation in a designed environment takes the form of being an audience, for example of a video, this is at the more ‘passive’ end of the spectrum, although this still requires participation, for example, in the form of being able to read and decode the meanings that the text or performance articulates. Because they are often multi-modal and multi-media, it is rare that designed environments call solely for an audience in this sense, which maintains a stage-auditorium relationship or a screen-auditorium relationship. Thus, many designed environments require a more ‘active’ form of participation, both at the level of physical movement and at the level of intellectual engagement which, in turn, may lead to emotional engagement and through that positioning to ethical and political engagement.

The term audience seems to imply that the person or persons attending remain still and/or seated, with the body disengaged from the intellect. At the level of intellectual engagement, a designed environment invites the participant to take part in the meaning production, not simply to receive a fully-developed moral or lesson, and be ready to learn, in which case the designed environment is also a learning environment with its own pedagogic strategies and techniques. It is through this combined physical and intellectual movement, with its various forms of synaesthesia, that a designed environment articulates its emotional import and its truth values, whether material, logical, emotional, ethical or political.

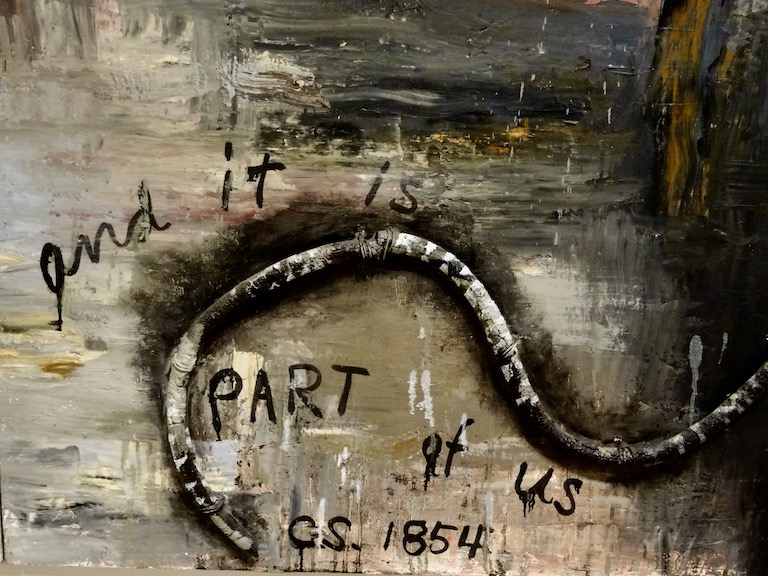

Thus, designed environments, because they do not often retain the stage-auditorium or screen-auditorium as a structuring binary division, encourage audience participation to varying levels, bringing the audience as a whole, or members of it, like some variants of experimental theatre since the 1960s, inside the performance, even to a level that could be considered a form of co-authorship. This has implications for the way we think about designed environments, where those who might be considered the audience are often inside the environment and therefore may, or may be caused to, experience the design as a narrative or a dramaturgy as if they are characters within it, becoming participants in the ‘performance’ or ‘realisation’ of the designed environment.

Even in conventional theatre, where the stage-auditorium divide is rigidly maintained, or indeed in the conventional classroom where the lectern-auditorium divide is similarly maintained, the audience has an effect on the performance. Actors and lecturers often talk about this effect, the way the energy and behaviour of the audience or the students affects their performance, hence giving rise to such notions as good, bad, lively, responsive or unresponsive audiences or students.

Note to follow up: audienceship, the appropriate way to behave as a member of an audience, is a learned behaviour: a theatre audience differs from a cinema audience which in turn differs from an opera audience; and all those from spectator sport audiences (spectators).

Political significance of ‘audience’ in the era of pervasive social media and the ubiquitous interactive screen

Daniel Ross (2018: 11) notes that “a polity of performatively-generated filter bubbles, of ‘audiences’ rather than citizens” has emerged in the 2010s. Such a system, “no longer conforms to the minimum requirements of ‘democracy’ understood as a representative system in which the power to make collective decisions resides in the demos”.

In this context, the ‘Trumpocene’ of 2016-2021 is “a ‘post-democratic’ worldless world in which collective decision becomes strictly speaking impossible, because truth itself, losing its effective actuality, has somehow come to seem an irrelevant and obsolescent criterion.”

References

Bennett, S. (1988) The role of the audience: a theory of production and reception. McMaster University. Available at: https://macsphere.mcmaster.ca/bitstream/11375/6827/1/fulltext.pdf (Accessed: 31 March 2019).

Ross, D. (2018) Introduction. In Stiegler, B. The Neganthropocene. London, UK: Open Humanities Press.