RELATED TERMS: Analepsis and Prolepsis; Arendt; Epic theatre – Brecht; Mimesis and Diegesis; Story (fabula) and Plot (sjuzet); Theatre; Theatre of Cruelty;

The importance of tragic theatre for design practices is threefold. First, it places great importance on plot construction and the effects upon the audience that such plotting can achieve. Second, it emphasises the importance of engaging an audience empathically, in relation to plot construction, in the context of moral and intellectual education. Third, like drama, the narrative in a design is embodied and enacted, woven into an experiential, intercorporeal, spatio-temporal framing. Much, therefore, can be learned about design practices from the construction of a drama. Engagement with and participation in a design, like drama, involves the weaving together of emotional and intellectual responses, together with reflection upon those responses.

The Western tradition of dramatic construction has been dominated by the Aristotelian conception of tragic drama. This was critically re-articulated by Bertolt Brecht, through his conception of epic theatre; and by Antonin Artaud, with his conception of a theatre of cruelty. The Aristotelian model has been further destabilised through the disruption of plot by the insertion of elements of reflexivity, the inclusion of devices that point to the deliberate constructedness or artificiality of the drama’s narrative, such as in the theatre of the absurd, and by the implications this has for the participant/audience.

Tragic theatre, as conceived by Aristotle, then, is important not just for its emphasis on plotting but also for its concern with the emotional and intellectual effects upon the participants and the proximity or distance which the participants are granted in relation to the narrative events unfolding. A number of questions may arise from adopting the Aristotelian approach to drama, and hence to designing. For example, there is the question, firstly, of whether it encourages critical thinking on the part of the audience, or simply delivers aesthetic pleasure as an end in itself, through catharsis; secondly, whether it permits an understanding of the social conditions of the protagonist’s actions, rather that a narrow focus on individual decision-making and action within a universal, ideal conception of the human condition; and, thirdly, whether the emphasis on emotional engagement helps or hinders the audience’s intellectual understanding of the drama’s significance and meanings.

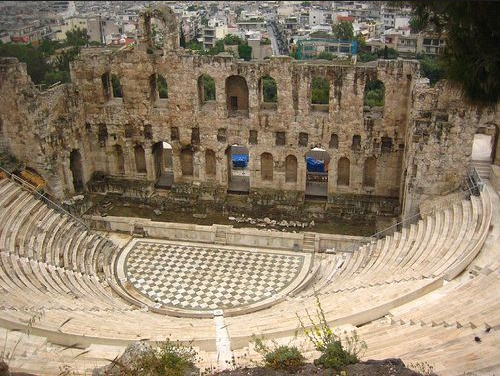

Greek tragedy was a popular and influential form of drama performed in theatres across ancient Greece from the late 6th century BCE (Cartwright, 2013). Working inductively, Aristotle developed his theorisation of tragic theatre from the works of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides.

Aristotle’s theorisation of tragic theatre is framed by wider debates in the Ancient Greek world about the role of the art-work (poiesis, making; and the work as poietic production) and the emotions in moral and intellectual education. The central issue for tragic theatre is whether emotional engagement with the characters in the drama help or hinder the audience’s critical intellectual reflections on the characters and situations represented in the work. For Plato, the emotions that tragedy evokes in the audience disables them intellectually and leads them astray morally (Curran, 2001: 167). Aristotle, at least in the interpretation of his work proffered by Martha Nussbaum and Stephen Halliwell, values tragic drama because it elicits emotions that work in conjunction with a cognitive understanding of ourselves as human beings and of the world in which we live (Curran, 2001: 167-168).

Curran (2001) brings into sharp focus Aristotle’s view, first, that plots must feature the individual error of an otherwise morally admirable protagonist; and, second, that engaging with the thoughts and feelings of the tragic protagonist is central to responding to tragedy. These practices, as Aristotle describes them, do not permit drama that is socially critical, unless they are supplemented by other devices that link the action of the protagonist to a larger social nexus. In this respect, Brecht’s recommendations for dramatic construction are useful for supplementing the potential failings in Aristotle’s preferred dramatic practices.

For Aristotle, tragedy has a final purpose or end, i.e. telos, which is to be an imitation or representation, i.e. mimesis, of action and human life. While Aristotle links mimesis to similarity, he argues, against Plato, that the artist-playwright does not just copy the shifting appearances of the world. Rather, the artist-playwright imitates or represents reality itself, and gives form and meaning to that reality. This mimesis is associated by Aristotle with a characteristic pleasure, that of experiencing the catharsis, i.e. relief from or purification of the pity and fear evoked by the tragic events. In addition, response to mimetic works involves, for Aristotle, a certain kind of emotional or intellectual learning. Aristotle does not elaborate upon this learning nor, indeed, does he expand in detail upon what catharsis involves.

While Aristotle distinguishes six elements of tragedy, i.e. plot, characters, verbal expression, thought, visual adornment and song-composition, the basic principle of tragedy for Aristotle is plot, or the imitation (mimesis) of action. For an action to be tragic, it must incorporate features capable of eliciting pity and fear to effect a catharsis of these emotions in the audience. Aristotle evaluates plot construction on the basis of which plot patterns best evoke the emotions of pity and fear. Aristotle’s account of tragedy and why it affects the audience appeals to a universal essence of human nature, such that the definition of certain events will elicit a response of pity and fear in anyone who witnesses the dramatisation.

Aristotle’s approach to tragedy is therefore essentialist in two respects: it is based on an account of plot as the inherent nature of tragedy; and it assumes a universal or idealised spectator, who will respond with pity and fear when witnessing the appropriately depicted suffering of the tragic protagonist. The best tragic plots in Aristotle’s view are those which show harm occurring, or about to occur, to kin or loved ones due to the tragic character’s not knowing what he or she is doing. In other words, as a result of the character’s falling unwittingly into error.

In Aristotle’s ideal tragic drama, then, the protagonist is basically a good person, a person ‘intermediate in virtue’ (Curran, 2001: 174), who brings about, or threatens to bring about, his or her own misfortune and those of his or her kin or loved ones, but who acts in ignorance of what he or she is doing. The suffering brought about is disproportionately greater than any error the character might have committed. It it is this incommensurability which allows the audience to feel pity and fear for him or her, a protagonist who, as ‘someone like ourselves’, we, the audience, can empathise and sympathise.

As a caveat, it should be noted that Aristotle draws on the class and gender hierarchies outlined in his Politics, such that, in his view, the goodness of a woman should be represented as inferior and the sufferings of a slave are not worthy of representation at all. In other words, tragic characters, for Aristotle, are male and are members of the aristoi or the oligoi, the noble or the wealthy classes.

References

Aristotle (2000). The Poetics of Aristotle, translated by H. Butcher. Pennsylvania, PA: Pennsylvania State University.

Cartwright, M. (2013). Greek tragedy. Ancient History Encyclopedia. Available from http://www.ancient.eu/Greek_Tragedy/ [Accessed 19 March 2016].

Curran, A. (2001). Brecht’s criticisms of Aristotle’s aesthetics of tragedy. Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 59 (2), 167–184. Available from http://www.jstor.org/stable/432222 [Accessed 25 June 2016].

Pedagogic journeys 1. Tragic drama as narrative, learning environment

This post complements a previous one on Modes of human actantiality, developing the implications of the work of Amelie Oksenberg Rorty for design practices in respect of the human dimensions of such designs. A design, especially if it is conceived as a narrative, learning environment, is a pedagogic journey, but it is not a simple passage from ignorance to knowledge. It may, indeed, be a process of unlearning, starting from a position of what has already been learned, and is presumed to be known: that into which one has been thrown. This process of unlearning leads to a means of learning otherwise in terms of ‘how’, ‘what’ and ‘why’. Another way of putting this, perhaps, is that ignorance and knowledge have many forms and are not mutually exclusive opposites.

It might be said that Western concepts of pedagogy, education and knowledge focus on character (ethe) [1] on ‘knowing oneself’ as ‘knowing how to act’ by knowing the plot, script or curriculum in which one has a role or plays a part, but a part apart, abstracted from the flow of events, a spectatorial or speculative way of knowing. This emphasis on co-implicated character and plot in pedagogy, education and knowledge is key to Western understanding of ethics and politics which are, for this reason, among others, constituted as narrative, learning environments.

Nevertheless, such character-plot focus still has the potential to open up to a recognition of the ‘essential’ or ‘vital’ relationality of pedagogy, knowledge and education, particularly when the notion of character is opened up to the structural relations of protagonist/antagonist and protagonist/amorist and related roles, such as helper and opponent, in the agonistic and erotic, i.e. relational, unfolding of the field of dynamic interaction, highlighting our existence as inter-related parts of ‘knowing’ and ‘belonging’ to ‘networks’ or ‘systems’ or ‘families’ or ‘communities’, at whatever scale.

Tragic dramas in the classical Greek mode show both the perils of going off-script, but, ironically, still within a well-plotted narrative, showing the devastation of erroneous waywardness (hamartia), but also of the lack of a guarantee that by staying on-script one has understood or knows ‘properly’ (to use an inadequate word) who one is. That is, tragic dramas point to the limits of self-knowledge, which is altered by changing the context in which such self-knowing, through action, takes place and is recognised.

The notion of changing context, symbolised through anagnorisis (moment of startling discovery, sudden movement from ignorance to knowledge), itself opens up to the notions of chance and contingency, as well as those of opportunity and opportunism and fortune and fortuitousness, but this, as Amelie Rorty (1992) explains, does not mean that its ethical lessons are primarily about the place of accident and fortune or fortuitousness in the unfolding of human life.

Plot and self-knowledge

A plot connects the incidents that compose it in three ways: causally; thematically; and by demonstrating the connections between the protagonist’s character, his thought and his actions (Rorty, 1992: 8).

Causally, the events of the plot are straightforwardly, simply and strongly linked. They are shown to happen because of one another. These causal connections must be necessary, or nearly so, as necessary as human actions can be, in order to link the events in a well-ordered whole and to elicit pity and fear.

The simplest types of thematic connection are repetition and ironic reversal. For example, Antigone lived to bury her dead; her punishment was to be buried alive. However, since she deliberately did what she knew to be punishable by death, she took her own life in the tomb where Creon had condemned her. Such patterned closures as this give thematic unity to a drama.

The unity of a plot is manifest in the way that each protagonist’s fundamental character traits are expressed in all that he thinks, says and does.

In the best plots, the peripeteia of action, i.e. the moment that reverses the protagonist’s fortunes, coincides with insightful recognition, i.e. anagnorisis (Rorty, 1992: 12), the startling discovery that produces a change from ignorance to knowledge. As Rorty comments, it is significant that this recognition typically fulfills the ancient command to ‘know oneself’ (gnothi season). She further explains that to know who one is, is to know how to act. Knowing how to act involves understanding of one’s obligations and what is important in one’s interactions (Rorty, 1992: 11). The cancer at the heart of the tragic protagonist’s hamartia, or erring waywardness, often involves his [sic] not knowing who he is, his ignorance of his real identity.

Action and character

Although tragedy, according to Aristotle, is about action and not character, the two are coordinate.

Character is expressed in choice (prohairesis) and choice determines action. Character is individuated and articulated in choice and thoughtful action. Life is action and activity. Tragic theatre represents serious action. It is also a dramatic representation of the way that the protagonist’s character is expressed through his choices and actions, which affect the way that his life unfolds. Acting wisely, acting on the basis of knowledge, requires making wise choices based on one’s obligations and the import of one’s interactions.

Catharsis and working through

The classical notion of catharsis combines several ideas, Rorty (1992: 14) explains. It is a medical term referring to a therapeutic cleansing or purgation. It is a religious term, referring to a purification achieved by the formal and ritualised, bounded expression of powerful and often dangerous emotions. It is a cognitive term, referring to an intellectual resolution or clarification that involves directing emotions to their appropriate intentional objects.

All three forms of catharsis are meant, at their best, to lead to the proper functioning of a well-balanced soul. In tragic drama, the psychological catharsis of the audience takes place through, and because of the catharsis of the dramatic action.

The Freudian psychotherapeutic expression working through is a lucid translation of many aspects of the classical notion of catharsis. In working through his emotions, a person realises the proper object of otherwise diffuse and sometimes misdirected passions. Like a therapeutic working through, catharsis occurs at the experienced sense of closure: emotional closure, completion or resolution, dramatic closure, narrative closure and pedagogic closure.

Pleasure and learning (learning as profound pleasure)

The pleasure of an action lies in its being fulfilled, i.e. completed as the kind of action that it is, with its associated values achieved. Tragic drama involves and conjoins so many different kinds of pleasure that it is difficult to determine which is primary and which accidental.

The pleasures that are specific to tragic drama are those that connect to the most profound of our pleasures, the pleasures of learning, with the therapeutic pleasures of catharsis, the pleasures arising from pity and fear through mimesis.

In recognising ourselves to be part of the activity of an ordered world, we take delight in self-knowledge, in the discovery that our lives form an ordered activity. When it is well structured and well performed, tragedy conjoins sensory, therapeutic and intellectual pleasure: pleasure upon pleasure, pleasure within pleasure, producing pleasure.

Drama and pedagogy 1: Pleasing and teaching: moral lessons and political significance

While tragedy pleases, it also teaches. Its lessons are moral, and its moral lessons have political significance. To choose and act wisely, we need to know the typical dynamic patterns of actions and interactions [to know oneself, who one is, is to know how to act, is to know the plot/script/curriculum and one’s role within it and one’s obligations within it]. For Aristotle, it is drama, of which tragedy is the highest form or genre, that ‘teaches’ moral and political truths, not history, the discipline which, for later moralists such as David Hume, was the source of such insights. In Aristotle’s day, historical texts were chronicles focused on particular events rather than on what can be generalised from them.

As well as teaching moral and political truths, tragic drama promotes a sense of shared civic life, in a similar fashion to well-formed rhetoric, and, like rhetoric, it does so emotionally and cognitively. Thus, tragic drama unites the audience, at least temporarily, in sharing the emotions of a powerful ritual performance; while it also conjoins the audience intellectually, bringing its members into one mind in a common world.

By presenting an audience with common models and a shared understanding of the patterns of action, tragedy, like philosophy and other modes of poetry, moves them beyond the individual or the domestic towards a larger, common, civic philia.

Drama and pedagogy 2: Tragic drama and chance

It has been said that, among its lessons, tragic drama teaches the power of chance and the force of contingency in determining whether the virtuous thrive. However, Rorty argues, while tragic drama does indeed focus on what can go wrong in the actions of the best of men [sic], its ethical lessons are not primarily about the place of accident and fortune or fortuitousness in the unfolding of human life.

For Aristotle, tragic drama is about what probably or inevitably happens. If, instead, the stressed lesson of tragic drama were the disconnection between intention and action, or between intention and outcome, it would produce sombre modesty and edifying resignation, traits which are not central to the Aristotelian scheme of virtues.

Tragic drama shows that what is central to excellence in action, what is intrinsic to the very nature of action, carries the possibility of a certain kind of arrogance and presumption. In acting purposively, people discount the tangential effects of chance and accident. Intelligent action sets aside what it cannot measure. Still, event of, in a general way, we sombrely recognise the contingency of our lives, this does not mean that people can avoid tragedy by becoming modest or resigned. It is in our nature to strive for what is best in us.

The lesson of tragic drama is not that we should know more, think more carefully. Nor is it that we should be more modest and less impetuously stubborn than the protagonists of tragic dramas. Because it is no accident that excellence sometimes undoes itself, one of the dark lessons of tragedy is that there are no lessons to be learnt in order to avert tragedy.

Drama and pedagogy 3: Transformations

Even so, for all that, the end note of tragic drama, its lesson, is not that of darkest despair. The major tragic figures emerge enlarged, transformed by what they have endured as well as by what they have learnt from their endurance, i.e. by the anagnorisis that is a double turning of their lives. Their fortunes are reversed in recognising who they are and what they have done. The mind becomes identical with what it thinks. Knowledge perfects the person. Thus, in the nobility with which they express their recognition, a nobility which fuses character with knowledge, tragic protagonists have become their best selves.

Tragic drama, for Aristotle, enacts the view that is philosophically expressed in the Nicomachean Ethics, whereby the virtuous can retain their nobility in the worst reversal of fortune, the loss of the goods that are normally central to eudaimonia, such as health, the thriving of their children and their city, wealth, the admiration of their fellows.

Tragic dramas portray the ethical doctrine that there is a sense, albeit not the ordinary sense, in which the constancy of virtue, the expression of nobility in the midst of great suffering can carry its own form of eudaimonia, despite the loss of goods that normally constitute happiness, as eudaimonia consists in the actions of a well-lived life, as perfected as it can be.

While the undeserved suffering of the virtuous elicit our pity and fear, the nobility with which they meet their reversals, a nobility manifest in their actions and their speech, illuminates us. In this way, the audience, like the tragic protagonist, are transformed by what they have seen and learnt by witnessing the dramatic stories of the tragic protagonists, participating in their final recognition.

Recognising what we are, recognising our kinship with those who over-reach themselves in action, we can become closer to fulfilling our natures and our virtues as knowers and as ‘citizens’, i.e. participants in a collectivity or collectivities of different scales, participants in various ‘worlds’ or various narrative, learning environments.

Rorty concludes: Since pleasure is the unimpeded exercise of a natural potentiality, our double self-realisation brings a double pleasure, all the more vivid because we are united, individually and communally, in realising that however apparently fragmented, ill-shaped and even terrible our lives may seem to us in the living, they form a single activity, a patterned, structured whole in the narrating, i.e. in the narrative, learning environment as pedagogic journey, from one ‘place’ to another through a passage of time and through a passage of space as in-between.

Until, that is, one learns to remain or to dwell in the in-between as the ‘now’ and the ‘null point’.

Notes

[1] Aristotle speaks primarily of agents or actors, prattontes, and of characters, ethe, not protagonists (Rorty, 1992: 19). Prattontes refers ambiguously to fictional characters, such as Odysseus, who appear in the Homeric epics and also in Philoctetes, on the one hand, and to the dramatis personae of a specific play. Ethe refers, firstly, to the dramatis personae of the drama, typified as the King, the Messenger, i.e. actants in a Greimasian sense, structural roles, and, secondly, to the specific character structures that affect their choices and actions, for example, as good, manly, consistent and so on.

Reference

Rorty, A. (1992). The Psychology of Aristotelian tragedy. In: Rorty, A., ed. Essays on Aristotle’s Poetics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1–22.