RELATED TERMS: Anthropology;

In anthropology, as discused by Victor Turner, liminality, from the Latin word līmen, meaning ‘a threshold’, is the quality of ambiguity or disorientation that occurs in the middle stage of rituals, defined as a psychic-temporal-physical space. At this moment, participants no longer hold their pre-ritual status but have not yet begun the transition to the status they will hold when the ritual is complete. During a ritual’s liminal stage, that is, in the liminal space, participants ‘stand at the threshold’ between their previous way of structuring their identity, time, or community, and a new way, which the ritual establishes.

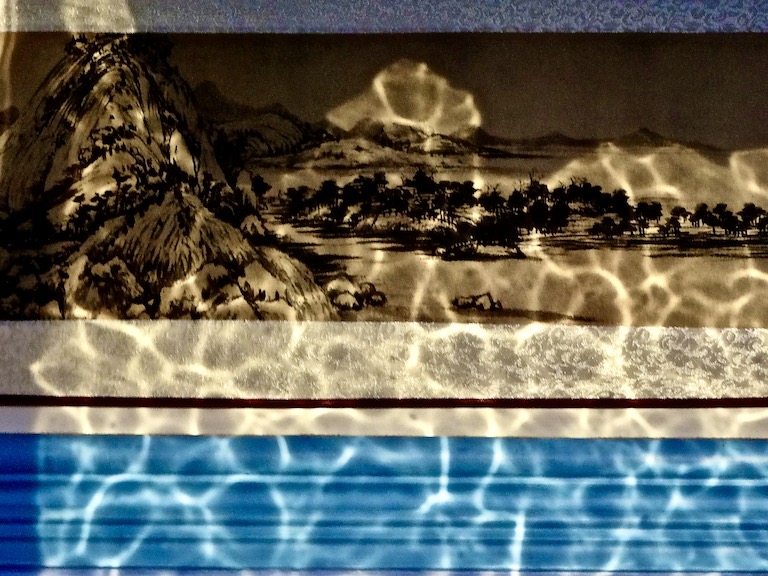

What is interest in the design of narrative environments is the condition of being in-between, or betwixt and between, the world of the story, on the one hand, and the world of the everyday, the lifeworld, on the other hand, which occurs when the participant generates and enters the storyworld instantiated by the narrative environment. In that sense, a narrative environment might be said to constitute a liminal space and progress through it similar to engaging in a ritual practice. Narrative environments may, however, only be ‘liminoid’ or ‘liminal-like’, rather than ‘authentically’ liminal, as Stephen Bigger (2009) discusses:

“The concept of liminality (the state of being on a threshold) was applied [by Turner] both to major upheavals and to performances generally, distinguishing only between ‘authentic’ liminality, and playful artifices such as the theatre which are named liminoid, or liminal-like. Liminality is viewed as an in-between state of mind, in between fact and fiction (in Turner’s language indicative and subjunctive), in between statuses. This concept has endured in performance studies and has the potential for wider usage.”

A liminal space can be a key component of a narrative environment. A liminal space can be either a physical or a temporal space, and often both at the same time, but it is always a psychic space.

Liminal spaces are places/times in which the audience is disorientated/moved from their normative assessment of ‘reality’ in order to prepare them for a different ‘reality’ presented in the main narrative space.

An account of a temporal liminal space is given by Daisetz Suzuki, a 20th century Zen Master, as cited by John Cage (1973: 88) in Silence:

“Before studying Zen, men are men and mountains are mountains. While studying Zen, things become confused. After studying Zen, men are men and mountains are mountains. After telling this, Dr. Suzuki. was asked, “What is the difference between before and after?” He said, “No difference, only the feet are a little bit off the ground.”

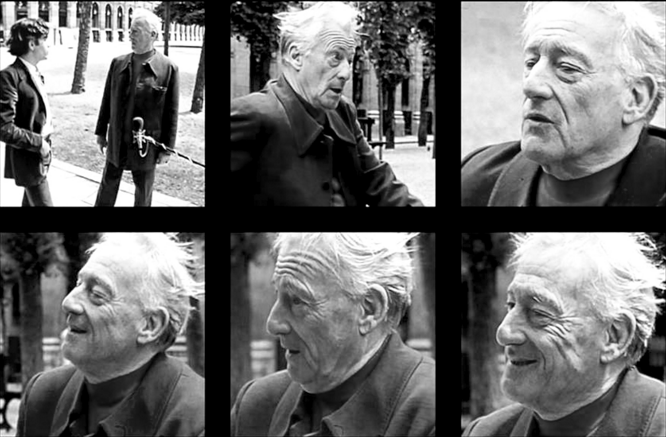

Victor Turner, 1920–1983, working with his wife Edith Turner, was an anthropologist deeply concerned with ritual both in tribal communities and in the contemporary developed world. Since the work of Turner in the 1960s, usage of the term liminality has broadened to refer to political and cultural change. During liminal periods of all kinds, social hierarchies may be reversed or temporarily dissolved, continuity of tradition may become uncertain, and future outcomes once taken for granted may be thrown into doubt. The dissolution of order during liminality creates a fluid, malleable situation that enables new institutions and customs to become established.

References

Bigger, S. (2009) Victor Turner, liminality, and cultural performance [Review of Victor Turner and contemporary cultural performance, edited by Graham St. John, New York and Oxford, Berghahn Books, 2008], Journal of Beliefs & Values, 30(2), pp. 209–212. doi: 10.1080/13617670903175238.

Cage, J. (1973) Silence: lectures and writings by John Cage. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press.

Thomassen, B. (2009) The Uses and Meanings of Liminality. International Political Anthropology, 2 (1), 5-28.

Horvath, A., Thomassen, B. and Wydra, H. (2009) Introduction: Liminality and Cultures of Change. International Political Anthropology, 2 (1), 1-4

Szakolczai, A. (2009) Liminality and experience: Structuring transitory situations and transformative events. International Political Anthropology 2 (1), 141-172