RELATED TERMS: Design and Philosophy; Design practice and Functionalism; Phenomenology; Genealogy – Nietzsche; Heidegger; Human Actantiality; Dasein; Epistemology; Ontology; Poeisis; Nihilism

“Where to begin in philosophy has always – rightly – been regarded as a very delicate problem, for beginning means eliminating all presuppositions.” (Gilles Deleuze, 1994: 129)

“The point is not to gain some knowledge about philosophy but to be able to philosophise.” Martin Heidegger, The Basic Problems of Phenomenology

“to philosophize is to be constantly engaged in the never-ending subversion of states of affairs and of systems of thought; it is to be constantly wary of any attempt to solidify the truth of a particular discourse into a privileged ideology whose structure is epistemically violent.” (Hernandez, 2014)

The word philosophy derives from from the Greek term philosophia which means love of knowledge, pursuit of wisdom or systematic investigation. It is a combination of two roots: philo-, meaning loving and sophia meaning knowledge or wisdom.

Philosophy, experience and questioning

Paraphrasing Susan Stephenson (1999: 5), we could argue that design enquiry, like philosophical enquiry, begins with challenges that arise concretely within the life of a particular individual, particular groups or particular societies. It proceeds through a process of dialectical confrontations with different responses to how these challenges can be defined and addressed.

The value of philosophy for design practices and analysis of design action is perhaps best demonstrated with reference to Gregory Fried’s (2011: 240) characterisation of philosophical practice. While acknowledging that there is no consensus on what constitutes philosophy, Fried suggests that philosophy can be thought of as having three moments, moments which are perhaps also present in design practice, as will be discussed below.

The first moment, as articulated by Aristotle in the Metaphysics, is that philosophy begins with a sense of wonder (thaumazein in Greek). That wonder is the experiencing of something as deserving or demanding our attention because it is delightful, puzzling and enticing. Equally, it could be argued that philosophy might begin with a sense of horror or trauma, which may be similarly demanding of our attention, but not for reasons of delight. The crucial point is that philosophy begins with experience and perhaps heightened experience of some kind.

The second moment is the formulation of a philosophical question, an act that requires an intense focus on precisely what is at issue in our wonder [or horror or trauma], as we open to and admit the questions that confront us out of our own individual lived experience, through the embeddedness of the self in the world. By posing questions, we begin to philosophise through what seizes us and what challenges our world. It is the form of the question which guides what may be considered an appropriate response.

The third moment is answering, albeit however provisionally, or responding to the question.This may involve reformulating the question in the process of responding to it. Modern academic philosophical practice tends to focus on this last moment. The proper work of philosophy is seen, from this perspective, to be the production of answers, in the form of rigorous arguments with clear conclusions. However, as Fried argues, fixating on the moment of providing answers as the sole or primary work of philosophy distorts the full scope of what thinking demands of us.

Parallels can be drawn between this characterisation of philosophical practice and design practice. These parallels might be recognised more readily if one takes Martin Heidegger’s (2009: 11) suggestion that,

“The two questions asked in philosophy are, in plain terms:

1. What is it that really matters?

2. Which way of posing questions is genuinely directed to what really matters.”

For design practice, those questions may need to be extended, to become 1. What is it that really matters, to whom, for whom, in what ways(s), in what situation(s), of what duration? 2. Which ways of posing questions or challenges are genuinely directed to what really matters to whom, for whom, in what way(s), in what situation(s), of what duration?

More generally, like philosophy, design practice is not simply problem solving or answer-giving (moment three in Gregory Fried’s scheme), although, similarly to philosophy, most contemporary design practice is focused on this third moment of giving answers to problems, i.e. providing design solutions. However, to echo Fried, fixating on this moment of providing solutions, in the form of constructed artefacts or designed systems with explicit functions or uses, as the sole or primary work of design distorts the full scope of what design practice, as a mode of thinking, demands of us.

Design practice, like philosophy, needs to work on all three moments. Without good design questions, that are founded in experience and heightened awareness such as moments of wonder, horror or trauma, and a questioning of that experience in relations to the processes of the material social, economic, political and environmental world, such proffered solutions may lead to situations that are even more problematic than the initial one.

Design practice, then, like philosophy, does not begin with the production of answers or solutions but rather with a sense of wonder, or perhaps sometimes horror or trauma, and the posing of questions arising from and within that experience. Crucially, it is the formulation of the design question or questions that is key to arriving at valuable ‘results’. The question does not determine the precise result but it does, however, orient the direction of design processes.

One question might be whether such philosophical or design thinking can be systematised or made into a method. In response, it could be said, as does Friedrich Schlegel in his Athenaeum Fragments, that philosophy is a way of trying to be a systematic spirit without having a system, a position similar to that of Hannah Arendt.

Conventional understandings of philosophy as discipline

More conventionally, students of Plato and other ancient philosophers divide philosophy into three parts: ethics, the principles and import of moral judgment; epistemology, the resources and limits of knowledge; and metaphysics, the rational investigation of the nature and structure of reality. While useful for pedagogical purposes, however, no rigid boundary separates the parts.

David Woodruff Smith (2013) states that traditionally philosophy includes at least four core fields or disciplines: ontology, epistemology, ethics and logic. He suggests that phenomenology can be added to that list. On that basis, he provides elementary definitions of the field of philosophy as follows:

- Ontology (Metaphysics): the study of beings or their being — what is.

- Epistemology: the study of knowledge — how we know.

- Logic: the study of valid reasoning — how to reason.

- Ethics: the study of values — how we should act.

- Phenomenology: the study of our experience — how we experience.

Other domains of conventional academic philosophical investigation are:

- semantics, the examination of the relationship between language and reality; and

- aesthetics, the examination of notions of sensory perception and beauty.

All of these domains, that is, ethics, epistemology, metaphysics or ontology, logic, semantics, aesthetics and phenomenology, may be of value in design practice, so long as the focus is not simply or solely on producing results, that is, problem solving, but also on experiencing and questioning.

This list of categories, it may be noticed, avoids any notion of politics and political philosophy. This is perhaps a further domain that is of interest to both philosophy and design practice:

- politics and the political: the examination of the ways in which social groups and societies theorise, organise and regulate themselves through cultural rules, norms, laws and systems of governnment.

References

Deleuze, G. (1994) Difference and repetition. Translated by P. Patton. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Fried, G. (2011). A Letter to Emmanuel Faye. Philosophy Today, 55 (3), 219–252. Available from https://www.academia.edu/2613554/A_Letter_to_Emmanuel_Faye [Accessed 29 August 2016].

Heidegger, M. (2009) Phenomenological interpretations of Aristotle: Initiation into phenomenological research. Translated by R. Rojcewicz. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Hernandez, M. R. F. (2014) Philosophy and subversion: Jacques Derrida and Deconstruction from the margins, Filocracia, 1(2), pp. 105–134.

Smith, D.W. (2013). Phenomenology. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available from http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/phenomenology/#5 [Accessed 5 September 2016].

Stephenson, S. (1999) ‘Narrative, identity and modernity’, in ECPR workshop ‘The Political Uses of Narrative’ Mannheim, 29-31 March, 1999, pp. 1–18. Available at: https://ecpr.eu/Filestore/PaperProposal/37fe9dc5-6ad9-4a73-b35a-704d8265ecb0.pdf (Accessed: 31 March 2021).

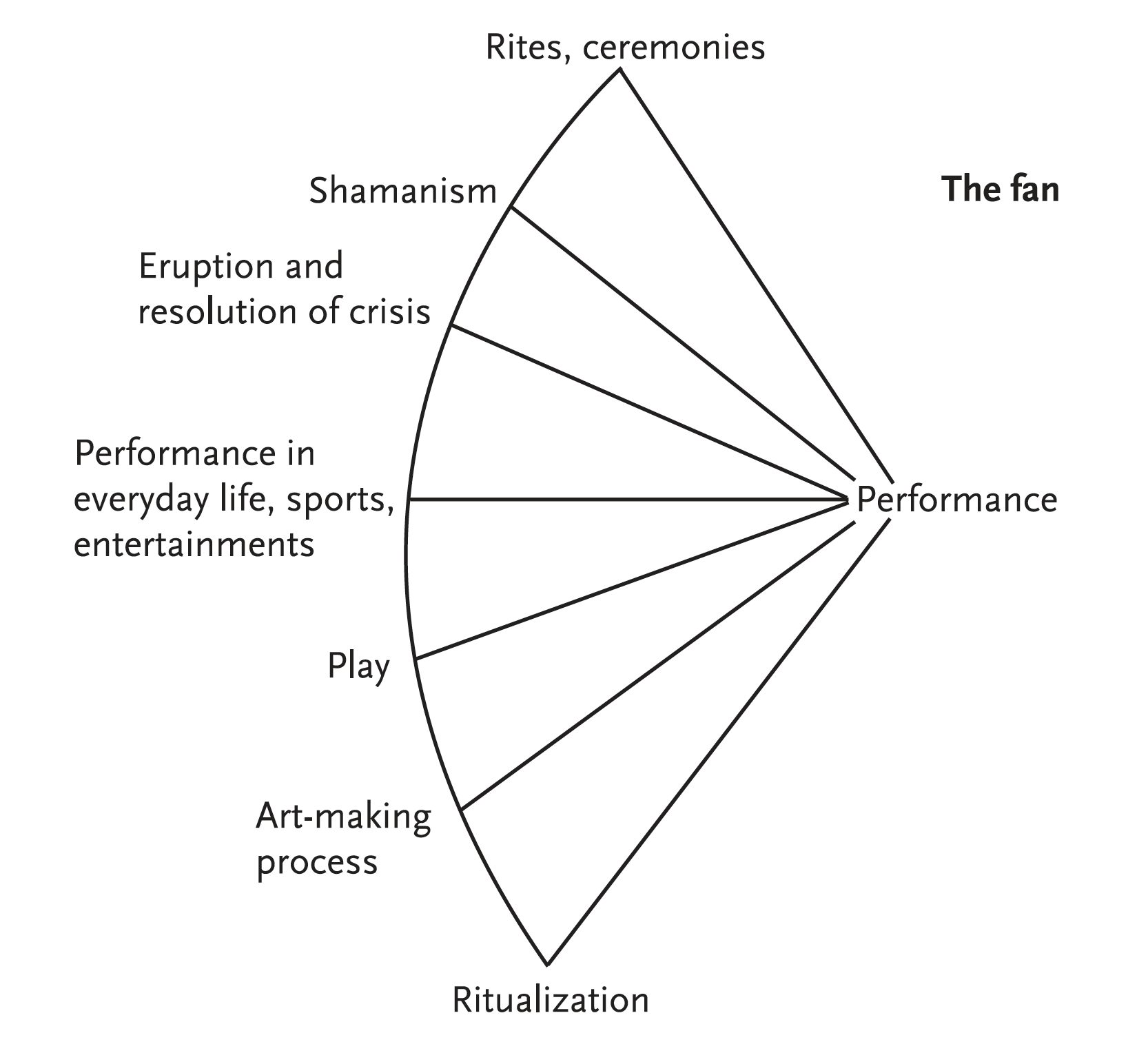

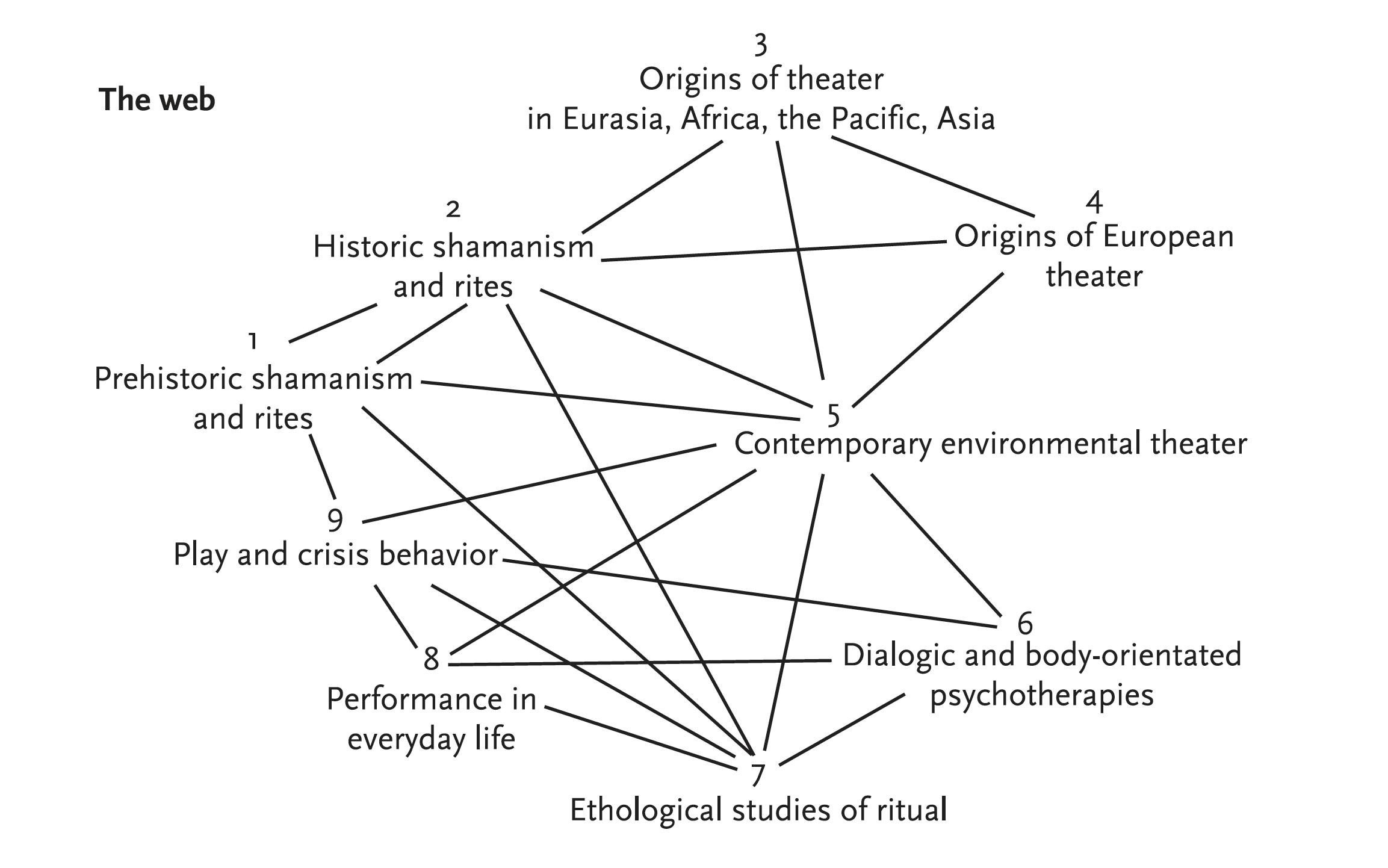

Source: Richard Schechner, Performance Theory

Source: Richard Schechner, Performance Theory Source: Richard Schechner, Performance Theory

Source: Richard Schechner, Performance Theory