RELATED TERMS: Place, Space, Placiality and Spatiality

From the perspective of design practices which incorporate thinking about the temporality of the design, the discussion of the relationships among the notions of narrative, time and the human by Paul Ricoeur (1984) may be useful. Ricoeur argues that,

‘time becomes human time to the extent that it is organized after the manner of a narrative; narrative, in turn, is meaningful to the extent that it portrays the features of temporal experience.’

(Ricoeur, 1984: 3)

The ancient Greeks had two words for time: chronos and kairos. Chronos means absolute time: linear, chronological and quantifiable. Kairos, on the other hand, means qualitative time: the time of opportunity, chance and mischance. For example, if you wake up because the alarm says it is 7.30am, you are adhering to a chronological time system (clock time). If you wake up because have had sufficient sleep, you are following kairological or event time (perhaps also circadian time).

The concept of rhythm become relevant here, especially in relation to generating and understanding possible worlds. This may concern rhythmic times within linear, unfolding times; reversible and irreversible time; recurrent and unrepeatable times; circular and linear directionality of time; time-asymmetry and time-symmetry.

In addition to conforming to clock time, we each have a sense of event time, which is at once subjective and culturally objective. With clock time, objectified time is outside the activity and regulating it; with the latter, the time of an activity is integral to the activity itself (Loy, 2001: 275). In this context, the thought of the Japanese Zen master Dogen, may be instructive for design practice. As Loy (2001: 275) explains, Dogen demonstrates that objects are time: objects have no self-existence because they are necessarily temporal. They are not objects as usually understood. Conversely, Dogen demonstrates that time is objects. Time manifests itself not in but as the ephemera we call objects, in which case time is different than usually understood. “The time we call spring blossoms directly as an existence called flowers. The flowers, in turn, express the time called spring. This is not existence within time; existence itself is time.” (Dogen, cited in Loy, 2001: 275)

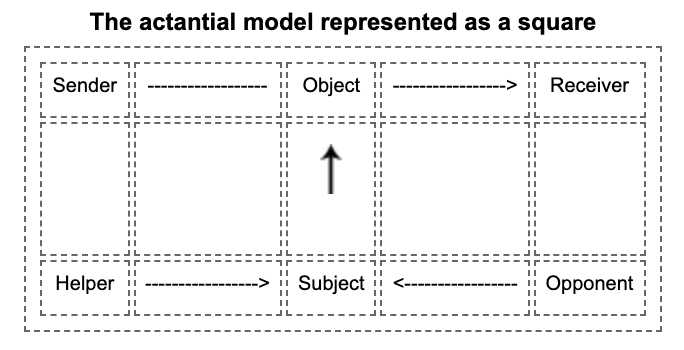

Hans Ramo (1999) discusses these two ancient Greek concepts of time along with their corresponding concepts of space, chora (or khora) and topos, in conjunction with the Aristoelian notions of action and the kind of knowledge with which those modes of action are associated: theoria (contemplation of universals) and episteme (knowledge of universals, ‘scientific’ knowledge); poiesis (making, producing) and techne (skill, know-how, proficiency); and praxis (action, inter-action) and phronesis (practical wisdom, judgement). He develops four possible time-spaces: chronochora (abstract time-abstract space), chronotopos (abstract time-meaningful space), kairochora (meaningful time-abstract space) and kairotopos (meaningful time-meaningful space).

The last term, kairotopos, might be taken as a definition of a sense of ‘place’ and ‘placiality’, where both the spatiality (my space, our space) and the temporality (my memory, our memory, my history, our history) are significant for a situated human being.

This bears on the discussion of the notion of ‘home’ (our space, our history) and whether one should presume that the fundamental human experience is that of ‘homeliness’ (being-at-home) or of displacement (being-at-odds), in relation, for example, to Heidegger’s notion of ‘being-thrown’, the ‘thrownness’ of being human. Perhaps it is the case that we are at once thrown into the known (tradition, what has unfolded and continues to unfold) and the unknown (futurity, what will unfold henceforth).

Carlo Rovelli: “If by ‘time’ we mean nothing more than happening, then everything is time. There is only that which exists in time.”

References

Loy, D.R. (2001). Saving time: a Buddhist perspective on the end. In Timespace: geographies of temporality, edited by Jon May and Nigel Thrift. London, UK: Routledge, pp.262-280

Ramo, H. (1999) ‘An Aristotelian human time-space manifold: from chronochora to kairotopos’, Time & Society, 8(2–3), pp. 309–328. doi: 10.1177/0961463X99008002006.time-meaningful place)

Ricoeur, P. (1984) Time and narrative. Volume 1. Translated by K. McLaughlin and D. Pellauer. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Rovelli, C. (2018) The Order of time. Translated by E. Segre and S. Carnell. New York, NY: Riverhead Books.

Thackara, J. (2005) In the bubble: designing in a complex world. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Wolf, W. (2003) ‘Narrative and narrativity: a narratological reconceptualization and its applicability to the visual arts’, Word & Image, 19(3), pp. 180–197. doi: 10.1080/02666286.2003.10406232.