RELATED TERMS: Design of Narrative Environments; Narrative Environments

Jan Golembiewski is an architect and neuroscientist working at Psychological Design, an architecture practice based in Sydney, Australia. His research investigates the psychodynamic significance of environmental action. He suggests that design, at all scales, from cities to buildings to interiors, down to the objects in them, prompt, motivate and ground human behaviour. In other words, design provides ‘affordances’ for human behaviour, human interaction and human community. Design, in this sense, is not the sole remit of ‘the designer’. We all practice design decision making in our homes whenever we make aesthetic choices.

Human-environmental interaction has been explored by cognitive science and environmental psychology. The work of John Bargh and James Gibson, for example, explores the insight that perception and action are completely intertwined. Perception is not a passive or reactive reception of data. Rather, it is an active, projective scanning of, and engagement with objects, people and environments. We attend to our surroundings selectively, acting on some aspects while ignoring others. We also adapt to our environments and use conditionally what is on offer. Design, by changing the features and arrangements of the environment, is capable of altering that attention and use.

However, we do not simply act in a particular way just because the opportunity to do so is apparent. The motivational power of designed environments is especially strong. This is because the designer’s every decision has the aim of making us do or feel something. To keep us safe and to protect us from diving ‘thoughtlessly’ into every opportunity we see, irrespective of the consequences, we have evolved cognitive breaks, in the form of the human neocortex. For the most part, the neocortex consists in inhibitory neural circuitry, unmatched in the animal kingdom in terms of relative size and complexity. For healthy people, most action is therefore inhibited. This inhibition deflects or ‘sublimates’ potential actions into feelings, memories and self-awareness so that when we walk to a cliff’s edge or an open window we do not jump, even if we may still recognise the impulse to do so. This phenomenon, which the French call l’appel du vide, or ‘the call of the void’, is central to Golembiewski’s neuroscientific research.

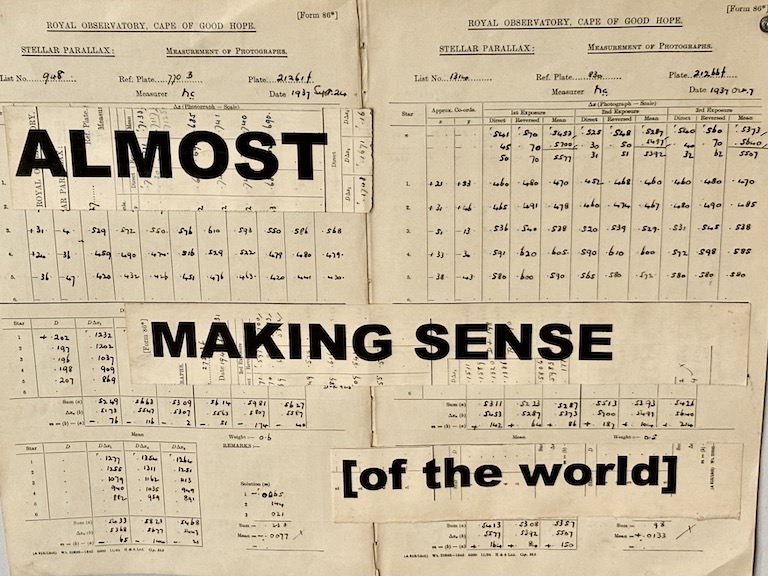

In a broad sense, design involves composing motifs and memes to make sense. One major way of making sense of environments, and responding to them, is through the stories they articulate, implicitly or explicitly. At Golembiewski’s architectural practice, Psychological Design, designs are conceptualised as stage sets, as a means for understanding the people involved and the circumstances they face. Taking such an approach leads to the posing of such questions as: what stage set is appropriate here?; and what narrative do we want to establish in this space?

If we think about the environment as a series of stage sets for an extended drama in which we are all the protagonists, we can begin to understand how deliberate design interventions can be introduced into the flow of human and collective behaviour, by calling for our attention and registering in our own reflexive and narrative understanding.

References

Golembiewski, J. (2022) ‘Haunted by design: how buildings can make us see ghosts’, Financial Times, 29 October.

Sudjic, D. (2006) The Edifice complex: how the rich and powerful – and their architects – shape the world. London, UK: Penguin Books.

Online resources

An interview with Jan Golembiewski on how the built environment affects our mental health can be found on the Centre for Inclusive Design website: