RELATED TERMS: Finnegans Wake (and Design); Methodology and Method

First …

Design as a professional, social practice has historically been divided according to its material outputs, its concrete products, using categories that have become conventional. For example, jewellery design produces items of jewellery, fashion design produces items of clothing and architectural design produces buildings and cities, with each domain incorporating a value hierarchy: there is good design and there is bad design. However, professional design practices have moved far beyond the creation and styling of commodities. They now include such domains as software development, ethnographic research and management consulting (Stern and Siegelbaum, 2019: 268); and even extend to the design of organisational structures and entire societies (Engholm, 2023). This makes design increasingly elastic and difficult to define. Its scope continues to extend because, as Buchanan (2001: 9) notes, “design is an art of invention and disposition, whose scope is universal, in the sense that it may be applied for the creation of any human-made product.”

In seeking to explain the historical development of design practices, Engholm (2023) argues that one could speak of a discipline-specific understanding of design, on the one hand, and a general understanding of design, on the other hand. In the discipline-specific understanding, design is primarily linked to the modern industrial age, with craftsmen employed to create concept designs and product prototypes for industrial mass production. It centres on a materially or artistically based intention to create a given form and is tied to traditional design disciplines, such as industrial design and graphic communication.

In the general or anthropological understanding, designs emerge from human responses, engagements and entanglements with their situations and their surroundings. In this perspective, all forms of tool use as well as projective action, action aimed at bringing something that does not yet exist into concrete, material existence, can be considered design.

The former understanding is more focused on material entitles as products and the processes required to make or materially realise them; the latter understanding is more focused on designs implemented in a field of interaction and the ongoing consequences in relation to societal goals and purposes, a more performative approach. They characterise two kinds of purposeful behaviour: a more limited sense of action that is productive and whose goal is pre-specified; and a more open sense of action that is interactive and whose goal remains open to continued reflection and reflexive alteration. In this contrast, the notion of ‘design intention’ shifts: from the material realisation of a plan or a concept in a fixed telic process; to the ongoing pursuit of a more abstract or ‘ideal’ goal that remains conditional or, in Derrida’s term, ‘to come’, an atelic process.

Since the 1990s, Engholm continues, traditional material, concrete, product design forms have been supplemented with more abstract forms. These include service design, interaction design and experience design. Furthermore, design studies and practices have emerged as a platform for innovation and strategy in business development. In emerging fields, such as speculative design, design futuring and transition design, which focus on moving complex systems towards more sustainable, equitable and desirable futures, design becomes a means for large-scale transformation on a societal level. Recognising such initiatives as design practices brings to attention an emphasis on values, notably sustainability, equity, justice and desirability, and the implicit axiological valuation articulated in prior design practices concerning usefulness, usability and desirability. What it also brings to attention is an acknowledgement of the malleability of ‘desire’, design practices having in the past been complicit in defining and altering what is considered to be ‘desirable’ societally and environmentally.

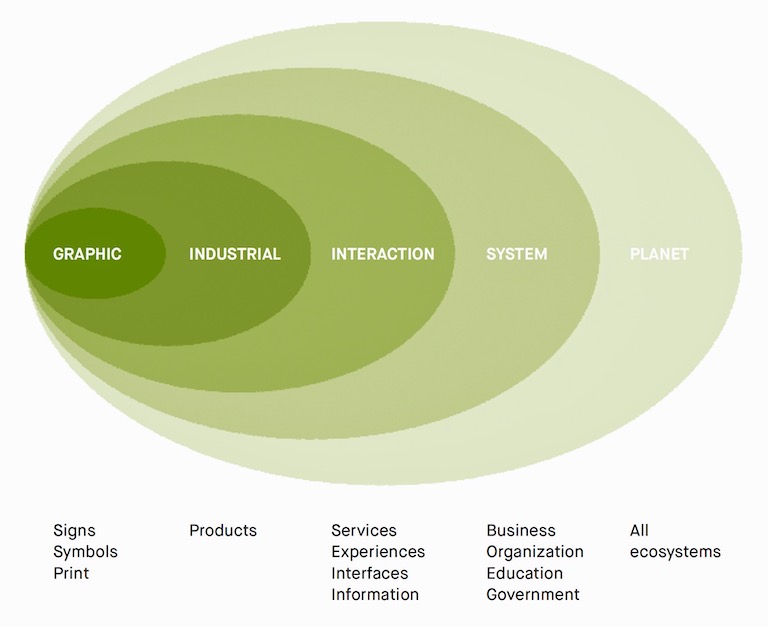

This historical development and expansion of design practices has been charactered as having four orders or dimensions by Richard Buchanan (2001), articulating, to different degrees, symbols, things, action and thought:

(1) design of visual representations, such as graphic communication (symbols);

(2) design of new products, such as industrial or product design (things);

(3) design of systems and services (inter-action); and

(4) design as method for organisational, political, financial or social development (thought).

Engholm proposes to add a fifth-order:

(5) design as an approach for handling the hyper complexity of challenges at a planetary-level (hyperobjects – Morton, 2013).

Engholm diagrams this set of orders as follows:

A sixth order could be added, which is in some sense a fractal image of the fifth:

(6) designs as interventions into quantum and microscopic interactions in chemical, biological, organic and ecological systems (nano objects).

It should be noted that each level of complexity does not erase the prior one, but each supplements the other in a complex, tangled hierarchy or ‘strange loop’ (Hofstadter, 1979). They all continue to be practised.

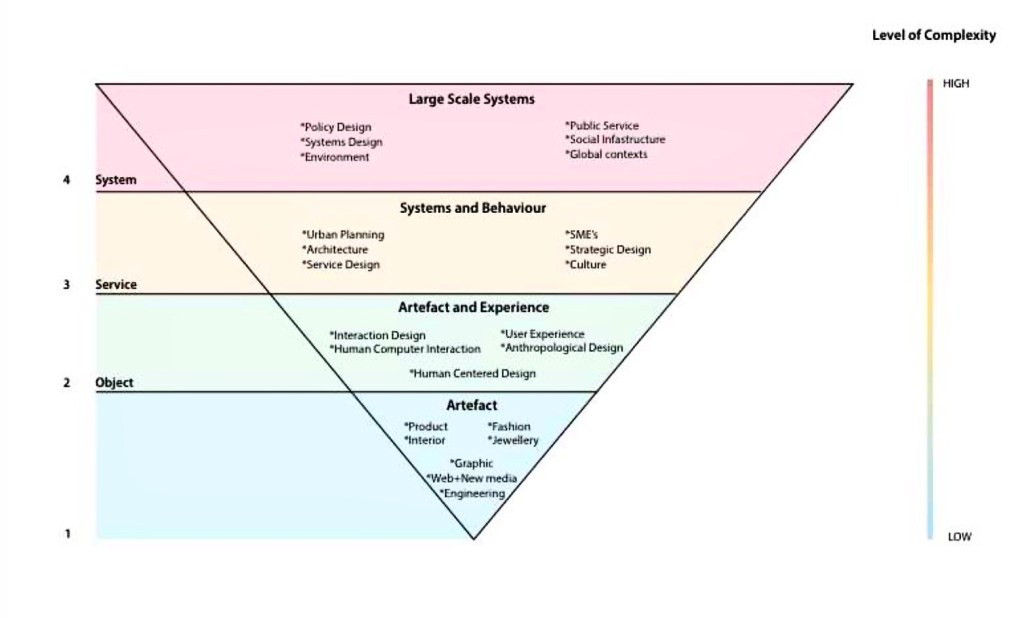

Similarly to Buchanan, Stefanie Di Russo (2016) has produced the following categorisation of design practices according to the level of complexity of their outputs, from object design, to service design to system design, practices to which design thinking can be and has been applied:

As part of understanding this historical development in the complexity of design practices, Stern and Siegelbaum (2019: 269) argue that, “much professional design since the 1970s has been unequivocally neoliberal and, additionally, that processes of neoliberalization are indebted to design”[1]. This is, again, to highlight the implicit ethical and political dimensions of design interventions as they are articulated in, and contextualised by, large-scale geo-political and geo-economic systems.

This is the first modality in which the term design can be understood which might be called, following Engholm, design-in-general or design in a global context. Here, we must take note of the contention that in the period defined as coming after the 2008 financial crisis, after the Covid-19 crisis and after the energy crisis set off by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, in short, ‘the present moment’ (as of 2025), neoliberal globalisation, may be on the retreat. Although it is far from disappearing, there is a noticeable return to the protectionist, state-interventionist, nationalist populism that marked the interwar period (1918-1939). This movement is discussed in the entry World as Geoeconomics and Geopolitics [Snippets 10]

Second …

Designs, the outcomes of professional practice, once made or implemented and distributed, structure the world in which we live. In this modality, design exists as a key element of everyday practices and as a material public discourse. It might also be called material culture, if taking an anthropological or art historical perspective, or public culture, if taking a more sociological and political perspective. However, paradoxically, because designs are so pervasive and so familiar, they become imperceptible in as far as they are taken for granted: ‘designs’ disappear into ‘life’. This is where the third modality of design comes into play.

Since design education has been incorporated into universities during the latter part of the 20th century, the academic disciplinary dimension of design practices has become more prominent. Not reducible to a mirror of design as a professional practice, although partly reflecting professional categorisations, design as academic discipline, firstly, opens a space for reflection upon the relationship between design as professional practice and the public agency or actantiality of design assemblies; and secondly, serves as a space for potential inter-disciplinary and trans-disciplinary collaboration outside of conventional design topics, leading to an emergent trans-disciplinary design curriculum.

Design as an academic discipline opens the question of the value of academic theorising. It may seem to take us away from recognising the value of design as social and professional practice towards a ‘theoreticism’. The first response to this question of the value of theory is to suggest that theory is unavoidable because, to paraphrase W.J.T. Mitchell (cited in Stiles and Selz, eds., 2012: 4)

” … everyone has a theory that governs their practice … the only issue is whether one is self-conscious about it.”

The first task for all of us then is to become more aware of the theories already at play in our existing practices embedded in the habits and intuitions that we use to guide our practice. Another aspect of this is that academic theorisation enables the above-noted ‘disappearance’ of designs through familiarity to be analysed so that the actantiality of designs, how they perform, instrumentally or otherwise, and what they do to us at the same time through interactive, dialogical performance, becomes foregrounded.

In other words, theory is not being imposed upon practice. It is already there. It is ‘given’. Explicit academic theorisation allows you to question, sharpen and refine the ‘givens’ of your habits and intuitions, perhaps to break a long-standing habit or to generate insights that are counter-intuitive. Theorising is vital for your creative development.

Third …

One central conjecture of Incomplete … is that design education is an important determinant of how design is realised as a social practice. Design as a social practice is a ‘pharmakon’, in Derrida and Stiegler’s sense: it is both a potential remedy and a potential poison.

Fourth …

Another conjecture is that the term ‘design’ is more appropriate than the terms ‘writing’, ‘media’ and ‘technology’ to define the ‘originary supplement’ that sustains humanity’s ek-sistence, its exosomatisation, whereby socio-genesis and techno-genesis are reciprocally intertwined.

Fifth …

Design as a social practice is a ‘khora’ or a différance, a third place neither here nor there, neither now or then, but both here and there and both now and then, a place of possible substitution; a third place and a non-place.

Sixth …

Design is a form of remembering or recalling, following Stieger’s argument about technology as a mnemotechnics. This is an important aspect of defining the affordances which enter into the determination of how people act, react and interact.

Seventh …

Design, therefore, inter-relates anthropogenesis, technogenesis and sociogenesis; and, as noted above, mnemogenesis.

Eighth …

Design, taken as a translation of the German word ‘Entwurf’ in the Heideggerian existential project, collects together: the thrownness of Dasein as a human condition; that into which Dasein is thrown, its situation; the forward-orientation of Dasein, moving through and within its situation; and its recall or active rememoration of what has been done and experienced, whereby the finitude of Dasein is negotiated.

Ninth …

Dasein is design, to use Oosterling and Sloterdijk’s phrase; to be human is to design. Dasein here is taken to mean both existence generally and human existence more specifically. Thus, if, as Colomina and Wigley (2016: 9) argue, the ambition of design practices, while presenting themselves as serving the human, is actually to re-design the human, the history of design can be taken as a history of evolving conceptions of the human: “To talk about design is to talk about the state of our species.”

Tenth …

If design practices concern evolving conceptions of the human, then the processes of designing and re-designing the human, by default, engage with the designing and re-designing of the complex adaptive systems, or webs of entangled living things, of which and in which the human is part. The design of narrative environments, in this context, may be defined as the design of complex adaptive systems.

Given these conjectures, design outcomes of whatever character, including the outcomes of design education, design practices and the accretion of past designs that make up the given or the taken-for-granted environment, intervene to re-articulate ‘worlds’ of various orders.

In this way, they form strange loops, in which consciousness and experience are crucially implicated, by intervening in the heterarchical organisation of ‘worlds’ of various orders, emphasising particular value hierarchies over others in a dynamic play. A ‘world’, in this approach, is a taken to be a heterarchy formed through the interaction of many hierarchies.

In practice, design outputs work as deictic cascades, establishing a deictic centre, a place which nevertheless may then be dis-placed in a number of dimensions. Through these deictic plays, designs are considered to be crucial for the exploration and understanding of how possible worlds exist, are sustained and may emerge.

Incomplete … seeks to provide a theoretical perspective or a philosophical stance upon design, as material cultural discourse, as professional design practice and as academic design discipline, that will inform not only the research methods and the methodology for the study of design but also for the practice of design: how designs are made and what they do in the short and the long term.

Human agency and action, as understood here, is entangled with other forms of being able to act, which is being called actantiality or potential to act. For example, the agency of things, the agency of stories and the agency of environmental forces, such as atmospheric dynamics and ocean circulation, all interact, with human action, sometimes deterministically, sometimes circumstantially, sometimes overwhelmingly.

Agency, or rather actantiality, is distributed throughout the world and is not solely of one kind or of one kind or magnitude. This insight has been discussed in terms of human and non-human actants, for example in actor-network theory; in terms of human and more-than-human actants, for example, in cultural geography, anthropology and ethnography; and in terms of human-technology relations, for example in science and technology studies.

Nor are such entanglements all of the same character. They may be multi-species entanglements, as brought to attention in discussions of the Sixth Extinction, geological entanglements, such as characterised by the term Anthropocene, or indeed quantum entanglements, from which these particular metaphorical notions of entanglement arise.

Design practices, from this perspective, are part of the actantial entanglement of the world. They intervene in the field of actantial potentiality, its actuality and its virtuality, perhaps to reinforce existing affordances or perhaps to alter them or indeed to create new affordances for action. Design practices can alter the conditions for action to occur, making certain concrete performances more or less likely.

Design practices, in this account, acknowledge the entangled character of the world and the performative means by which particular worlds are enacted into existence or emerge. Design practices do not disentangle but entangle otherwise, while taking responsibility for the performative consequences of that action.

Methodologically, this may be called a performative or an actantial approach within a post-Humanist or an environmentalist horizon. It is part of a more general move to de-centre the human from explanations of how life forms and worlds emerge, adapt and evolve.

The key terms in this approach, apart from action and agency include:

- entanglement, with its emphasis on relationality and interdependence;

- actantiality, with its emphasis on actuality and virtuality or potentiality;

- affordances, with its emphasis on opportunities and openings; and

- performativity, with its emphasis on systems and norms and performance, as a discrete, concrete instance of participatory action and interaction.

- Historicity and futurity, in relation to an ongoing situation in which historical determinants circumscribe how inter-actions are perceived and acted upon

Together, they are valuable for understanding the net-working performed by designing and designs.

Notes

[1] The relationship between design and neoliberalism is explored by such scholars as Karen Fiss (2009), Ahmed Ansari (2017), Guy Julier (2017) and Lilly Irani (2018).

References

Ansari, A. (2017) The Work of design in the age of cultural simulation, or, decoloniality as empty signifier in design. Medium. https://medium.com/ @aansari86/the-symbolic-is-just-a-symptom-of-the-real-or-decoloniality-as-empty-signifier-in-design-60ba646d89e9 (Accessed: 30 July 2025)

Buchanan, R. (2001) Design research and the new learning, Design Issues, 17(4), pp. 3–23. doi: 10.1162/07479360152681056.

Di Russo, S. (2016) Understanding the behaviour of design thinking in complex environments [PhD thesis]. Swinburne University of Technology. Available at: https://figshare.swinburne.edu.au/articles/thesis/Understanding_the_behaviour_of_design_thinking_in_complex_environments/26292853?file=47659087 (Accessed: 19 July 2025).

Engholm, I. (2023) Design for the new world : From human design to planet design. Bristol, UK: Intellect.

Fiss, K. (2009) Design in a global context: Envisioning postcolonial and transnational possibilities.” Design Issues 25 (3), pp. 3–10.

Hofstadter, D. R. (1979) Godel, Escher, Bach: an eternal golden braid. New York: Basic Books.

Irani, L. (2018) Design thinking: Defending Silicon Valley at the apex of global labor hierarchies.” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience, 4, pp. 1–19.

Julier, G. (2017) Economies of design. London: Sage.

Morton, T. (2013) Hyperobjects: Philosophy and ecology after the end of the world. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Stern, A. and Siegelbaum, S. (2019) Special Issue: Design and neoliberalism, Design and Culture, 11(3), pp. 265–277. doi: 10.1080/17547075.2019.1667188.

Stiles, K. and Selz, P. (eds) (2012) Theories and documents of contemporary art. 2nd edn. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.