RELATED TERMS: Narrative Architecture; Incompletion

“Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s [novel] The Pledge (1958) … is about the inability of an ‘expert system’ (the police) to solve the ‘problem’, that is, a mysterious crime. Dürrenmatt’s work is all about the demise of rationality and the triumph of chaos. Acknowledging this tragic fact, my book [What Design Can’t Do] proposes to get rid of the distinction between design (all about order), and bricolage, which has to do with dealing with the mess out there.” (Lorusso, 2023b)

“the designer is … a bricoleur – a person who makes do with what they find, in the conditions in which they find themselves.” (Lorusso, 2023a)

The issues at stake here concern the value of montage, collage, assemblage and bricolage: as methods of construction for design; and as methods of understanding how design acts in the world. What is also at stake is the status of design in the context of both the poietic aesthetics of the ‘work’ and the political praxis of the ‘act’:

- in relation to the work of art;

- in relation to the discussion of the differences between art as work and art as event;

- the relation of design to modernism and avant-gardism; and

- the relation of design to avant-gardism as anti-art.

Is there such a phenomenon as anti-design, analogous to anti-art? If so, what is its historical trajectory?

Bricolage

Christopher Johnson (2013: 44) argues that,

“If one were searching for an appropriate metadiscourse for the description of the processes of bio-neurological and technological evolution, it seems that the technical metaphor of bricolage would in fact provide a more effective means of conceptualising these processes than Stiegler’s more abstract notion of differentiation. As the molecular biologist Francois Jacob puts it, evolution as bricolage is the ‘constant re-use of the old in order to make the new’ (Levi-Strauss 2009: 50).”

The argument being developed here is that design practice is best understood through processes of bricolage. Designs seek to re-work or un-throw the already existing, as the found within the given, to articulate new projects, projections and trajectories. Designing begins from the ongoing projections of those trajectories into which we have been thrown and in which we remain entangled. The principles through which design operates in this schema are thrownness, entanglement, foundness and givenness, understood dynamically as trajectories with an ongoing momentum to which appropriate responses must be found. Over time, designs articulate spatio-temporal bricolages, whose eventful historicity is marked by momentary assemblages.

Montage and Collage

“The collage technique, that art of reassembling fragments of preexisting images in such a way as to form a new image, is the most important innovation in the art of this [the 20th] century. Found objects, chance creations, ready-mades (mass-produced items promoted into art objects) abolish the separation between art and life. The commonplace is miraculous if rightly seen, or recognized.”

(Simic, 1992: 18)

The following is a summary of the montage and collage section, pp.31-40, of David Graver’s book, The Aesthetics of disturbance, with some suggestions as to the relevance of these methods of construction for design practices.

Not all theorists agree on the subtle differences between montage and collage. However, Graver suggests that there is some agreement about their principles of construction.

In montage, disparate fragments of reality are held together and made part of the work of art by the work’s constructive principle. All elements are related rationally to the whole, despite the heterogeneity of their sources.

While Graver is discussing the ‘work of art’, it is argued here that what he says holds true for ‘works’ of design, whatever their material form, or indeed their degree of immateriality.

In collage, the fragments of reality are not fully integrated into the representational scheme of the work of art. Unsubjugated elements of their external life shine through and disrupt the internal organisation of the piece.

If this insight is extended to the work of design, the dynamic may be reversed: designs, while conventionally taken to be part of the quotidian world, can disrupt the flow of the everyday by incorporating some unsubjugated representational qualities borrowed from the work of art. In this way, a dialogue can be set up between the meaning-generating regimes of art-forms, as internal organisation evoking of aesthetic wholeness or closure, and everyday utility, as contextual responsiveness evoking open-endedness or unendingness. Such dialogue, as competing interpretive modalities, may be valuable for particular forms of design practices which seek to bring into relationship ‘higher’ purpose, for example, ethical social interaction, and ‘mundane’ operational purpose, for example, cooking a meal.

At a methodological level, this opens up the question of the relationship between perception and interpretation, of what one perceives as already interpreted and the co-existence of different modes of perception-interpretation. It also opens up the question of whether there exists a hierarchy of modes of perception, with the ‘visual’ at the top, allied to the insight that there can never just be visual perception on its own. It is always part of a recognised or unrecognised synaesthesia.

In montage, the principle of construction uses elements of the external world to undercut and to put question the principle of imitation (mimesis, representation). For design, again, this may be reversed. Elements of imitation (mimesis, representation) may be used to undercut and to put in question the commonplace understanding of the external world. By implication, this changes the status of any particular ‘design’. It is no longer simply grasped as part of the quotidian external world, in other words, fully understood through ‘use’.

In collage, the principle of imitation uses elements of the external world to undercut the principle of construction: the extreme of imitation is the presence of the object itself. The implications for the methodology of design practices is that designed ‘objects’, of whatever material or immaterial form, are at once: utilities, whose meaning is exhausted through its use; self-referentially mimetic, in as far as they stand for themselves as indexical or iconic signs, in Peirce’s terms; and symbolic, in as far as they are part of a cultural landscape or ecosystem of entities whose meanings are differential or relational. In this way, designs can be both central to the operation of the everyday and liminal to that mode of understanding the real by drawing upon different approaches to interpretation the world. Like collages, designs may emphasise the radical heterogeneity of their elements. The unprocessed or unsubjugated elements of the external world within a collage have been alienated from their original circumstances but have not settled within the frame of the artwork. From the perspective of design, the unprocessed or unsubjugated elements of the mimetic world within a design have been alienated from their original circumstances but have not settled within the frame of the design. In Derrida’s (1994) terms, designs are artifactual and actuvirtual.

While the artwork strips away the quotidian context of meaning and use from the heterogeneous objects, transforming them into aestheticised objets trouves [found objects], the foundness of the objects points persistently back to the world from which they came and endows them with a disruptive autonomy from the formational powers of the artwork. In reverse, the design redoubles, sets trembling or sets oscillating the quotidian context of meaning and use by incorporating aestheticised modes of mimesis, representation and reflection into that quotidian context itself. If there is a mode of transportation or transformation it is both towards and away from the quotidian.

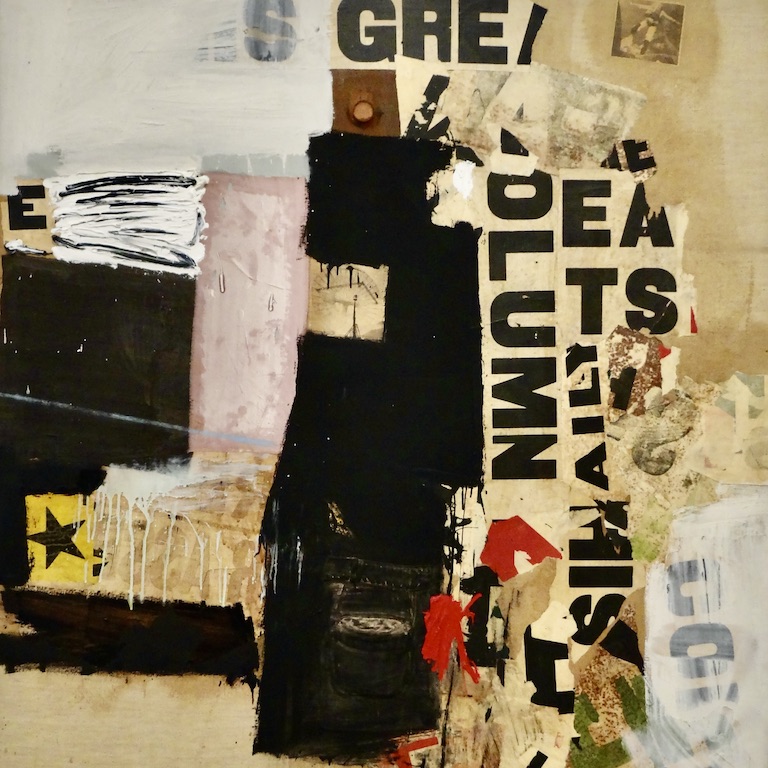

At an extreme, the process of collage seeks to subordinate direct reference to the world and the indirect references of artistic creation in order to highlight the unmediated presence of material objects, the singularity of the manifestation. Lindner and Schlichting define this form of collage as ‘material image’ (Materialbild) and take the work of Kurt Schwitters to exemplify it. The material it forms is no longer strictly aesthetic. External objects such as, for Schwitters, ticket stubs, buttons, spools and bits or wood or wire have been reduced to an unmediated materiality. The paint and gesso have also been transformed from their aesthetic materiality into a more immediately object-like existence. This ‘unmediated presence’, of course is paradoxical, as Lindner and Schlichting’s terms suggests: it mixes materiality with mimesis, ‘object’ with ‘representation’. The attempted subordination to singular presence is constantly in danger of unravelling into utilitarian object-hood, mimetic imagery or an oscillatory vibration between both, all of which are forms of ‘mediation’ or ‘relationality’.

The creative process, the process of forming, while tied to the productive skills of the maker, has abandoned the historically mediated development of artistic expression to play at gluing together the detritus of daily existence. Thus, in collage, paint becomes another found object and the painter becomes a bricoleur. Both the surface of the artwork and the process of the creation are made more immediate and concrete than in the realm of conventional art or high modernist art.

In montage, the emphasis is on construction rather than on the concrete materiality of the objects. Collage construction allows the parts to shine forth in their heterogeneous individuality. Indeed, they are more themselves than they could be in daily life. In montage, the individual elements participate in a project that is greater than themselves. Nevertheless, this project differs from the expressive unity of conventional and high modernist art in that the heterogeneity of the elements is not suppressed. Rather, the disjunctions and inconsistent material juxtapositions of montage contribute to the unifying purpose of the work just as much as the homogeneous material in conventional art does.

The unity of montage is an artificial one. Montage flaunts the cohesive power of its constructive procedure through its intentional incompleteness. In its incompleteness, montage establishes irreverent connections in three dimensions:

- Among the elements of which it consists;

- With the sources from which these elements are drawn; and

- In relation to the central purpose that holds the elements together.

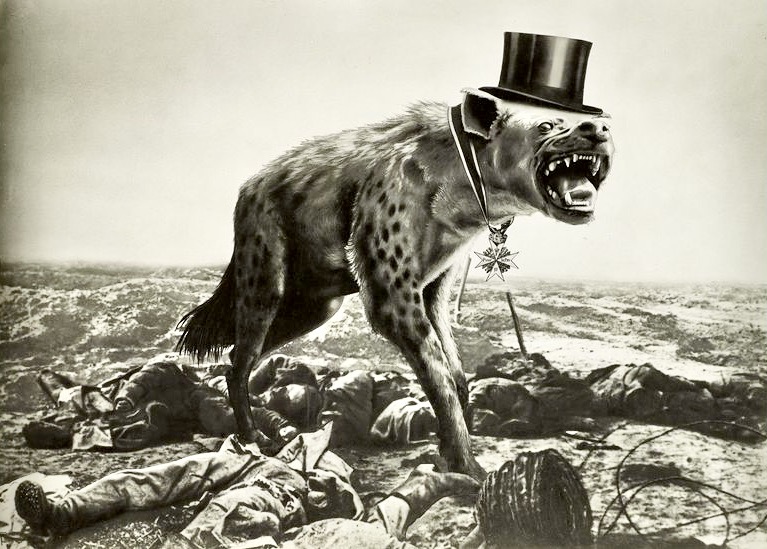

The common dynamics of montage can be seen in the very different uses made of their constructive principle by John Heartfield and Max Ernst. The central purpose of Heartfield’s work is political. Therefore the elements of each work always join in a pointed comment on a contemporary social issue. The example that Graver discusses is ‘War and Corpses – the last hope of the rich’. Both its disparate sources and the artificiality of its juxtapositions contribute to its political message.

The resort to photo-montage for Heartfield is necessary because a single photo-graph could not simply document the relationship between the war dead and corporate profits, two distinct realms of material social reality. Such complex chains of interconnection require extensive explanations which the photo-montage succeeds in short-circuiting.

However, in Heartfield’s photo-montage, it is important that each element is a photo-graph because they affirm the reality of those distinct realms of material social existence, notably:

- The forlorn battlefield corpses;

- The self-satisfied grandeur of a ruling class bedecked with formal hats and jewel-encrusted medals; and

- The existence of vicious animals that feed on the dead.

In transforming the hyena’s reality into allegory, Heartfelt entangles the reality of the battlefield and the reality of the capitalists while at the same time condemning that entanglement. Thus particular photo-montage documents visually the reality of the social situation by demonstrating it gruesome character. Through deixis, they rhetorically bring a complex, entangled field of social relationships to a singular moment of ‘presence’.

In this way, the formal entanglements of photo-montage stand as allegories of the entanglement of socio-cultural and socio-economic reality.

In the case of Max Ernst, unlike the collages of Schwitters or Pablo Picasso, the foreign elements within the image frame of Ernst’s picture books do not disrupt the integrity of the work with their persistent foreignness. Similarly to the work of Heartfield, the foreignness assists in creating the unique reality of the work. While Heartfield’s images appeal to the reality of a particular political discourse, Ernst’s images make more ambiguous references to various social, psychological and cultural forces.

Ernst’s ‘Drum roll among the stones’, while made from 19th century engravings, is nevertheless similar in may respects to Heartfield’s ‘War and Corpses’. On a battlefield depicting an explosion and fleeing soldiers, Ernst has placed a sedate bourgeois gentleman in the lower centre of the scene, looking calmly at the viewer, unaffected by the explosion. The individual elements still make reference to their origins: the sensationalism and formality of 19th-century mass-produced art. Yet they seem to have joined together in a hallucinatory, spectral reunion of dead images.

Ernst’s construction of the logic of the scene suggest more contemporary references which exceed the simple montage of outdated engravings. It could be argued that Ernst has depicted, from a different perspective that is no less incisive, the same modern problem that concerns Heartfield. Rather than explain the causes of state terrorism, Ernst displays the tranquility of an assassin.

The differences between Heartfield’s and Ernst’s montages have less to do with the constructive method employed than with the extent to which the central purpose in which the assembled heterogeneities participate is predominantly figural or discursive. Heartfelt is intent on telling a particular story. His montages have messages. They are held together by a discursive line of reasoning. Ernst’s montages do not make heir intentions clear. The viewer can never be entirely confident of the validity of their reading in respect of a presumed authorial intent.

Ernst’s montages participate in the disturbing silence of the anti-art avant-garde, a ‘silence’ that one might equally describe as a cacophony of noise, an absence of meaning as a multiplicity or over-abundance of meanings, seemingly unanchored deictically or intentionality. In contrast, Heartfield’s messages exclaim loudly the explicit political ideals of the partisan avant-garde.

The partisan avant-garde

The partisan avant-garde stakes its right to exist on a particular reading of the world to which it adheres. The anti-art avant-garde stakes its right to exist on the sensuous discomforts and delights of ambiguous presences, the immediacy of the figure and multiple worlds to which the figure might call us or, in Althusser’s terms, interpellate us.

All art contains both figural and discursive elements. The visual impact of Heartfield’s “War and Corpses’, for example, cannot be reduced to its discursive condemnation of capitaism’s fondness for war and profiteering. The images of his photo-montages expand beyond their explicit discursive messages to assert a figural presence that arises from the immediate density of the visual field.

In Heartfield’s montage, the figural presence can be sensed in the compelling juxtaposition of:

- The hyena’s voracious snarl;

- The comic quality of the top hat and medal;

- The poignant victimhood of the corpses;

- The anger of the caption; and

- The bold appearance of the image spread across two facing pages.

Although the figural element of the image spreads beyond the discursive element, it does not escape the discursive closure around a determinate statement or message. Word and image, or discourse and figure, in Heartfield’s case, are fused into a theatrical gesture, rather than simply a message. While the message takes precedence, the viewer understands it so clearly because of the figural density and the weight, or force, of the artistic gesture that hurls it at them.

The anti-art avant-garde

The anti-art avant-garde also fuses word (discourse) and image (figure) into a kind of gesture. However, because anti-art is more ambiguous or contradictory, or perhaps paradoxical and aporetic, in its deployment of discursive elements, the gesture is more disconcerting. The viewer does not know from whence it comes: who speaks? From whence? To whom? When? Where?

There is no clear message to which to respond: to agree, to disagree, to concur, to reject, to dismiss, to disavow, and so on. The viewer is confronted more noticeably with the discomforting presence of ‘mute’, or ‘white noise’, figural intensity. It becomes difficult to define the encounter in discursive terms, for example, when does it end? The encounter does not have a discrete beginning, middle or end, discursive closure or logical conclusion. The discursive elements are too fragmentary to cohere a formal discourse. Such anti-art photo-montages do not ‘speak’ discursively, yet neither are they ‘silent’. Rather, they are mute-ations of discourse (Graver, 1995: 38).

Collage and montage represent two extreme poles between which lies a continuous band of constructive possibilities.

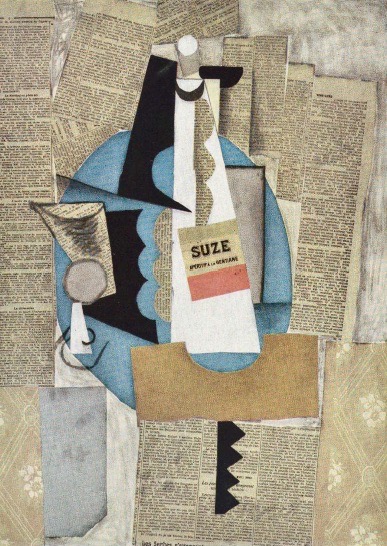

Schwitters’ work is a pure instance of collage. Picasso displays a collage sensibility in his emphasis on the material textures of objects and their references to their past lives. However, he sets the material immediacy of his collage elements off against the representational impulses of the picture plane. In Picasso’s ‘La Suze’ (1912), for example, the layering of paper strips, newsprint, wallpaper and a bottle label is similar to the celebration of quotidian detritus in Schwitters’ ‘Aufruf’ (1919).

However, in Picasso’s picture, the cut-out shapes figure forth a tabletop, bottle and glass, while the past life of the glued-down elements suggest the scene their shapes depict: the bottle-label, newspaper and wallpaper could be common objects from a Parisian cafe-bar. The collage elements of this work do not completely submit to the scene they depict, as in montage, but they do nevertheless flirt with the possibility of such a submission. Thus, Picasso’s collage constructions move provocatively towards the possibilities of montage.

Ernst’s montages are haunted by subdued suggestions of collage in that they celebrate the world of book engravings more persistently and disruptively than Heartfield’s montage elements draw attention to their origins.

If one takes as a requirement for ‘aesthetic’ work the notion of mastery over artistic themes and materials that are accepted as legitimate by conventional and high modernist art forms from 1919-1929, then the radical heterogeneity of collage during that period is inherently anti-aesthetic. Heartfield’s photo-montages, for example, violate the conventional social functions of art by placing art at the service of proletarian political causes. Montage, in contrast, can be either aesthetic or anti-aesthetic.

References

Derrida, J. (1994) ‘The Deconstruction of actuality’, Radical Philosophy, 68 (Autumn 1994), pp. 28–41. Available at: https://www.radicalphilosophyarchive.com/issue-files/rp68_interview_derrida.pdf (Accessed: 3 April 2020).

Dezeuze, A. (2008) Assemblage, bricolage, and the practice of everyday life, Art Journal, 67(1), pp. 31–37. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20068580 (Accessed: 24 April 2016).

Graver, D. (1995) The Aesthetics of disturbance: anti-art in avant-garde drama. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Johnson, C. (2013) The Prehistory of Technology: On the Contribution of Leroi-Gourhan. In Christina Howell and Gerald Moore (eds.) Stiegler and Technics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 34-52.

Kaprow, A. (1965) Assemblage, environments and happenings. New York, NY: Abrams.

Lorusso, S. (2023) What design can’t do: essays on design and disillusion. Eindhoven, NL: Set Margins.

Lorusso, S. (2023b) Silvio Lorusso recommends six books that destabilize design, Scrtaching the Surface. Available at: https://scratchingthesurface.fm/stories/2023-12-14-what-design-cant-do/ (Accessed: 29 March 2025).

Rowe, C. and Koetter, F. (1978) Collage city. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Shields, J. A. E. (2014) Collage and architecture. New York, NY: Routledge.

Simic, C. (1992). Dime-Store Alchemy: The Art of Joseph Cornell. Hopewell, NJ: The Ecco Press.