RELATED TERMS: Actantial model – Greimas; Narratology; Poststructuralism; Semiotics; Sculpture;

“In short, the very manifesto of structuralism must be sought in the famous formula, eminently poetic and theatrical: to think is to cast a throw of the dice [penser, c’est e’mettre un coup de des].”

Deleuze, G. (2004) ‘How do we recognise structuralism?’, in McMahon, M. and Stivale, C. (trans.) Desert Islands and Other Texts 1953–74. Los Angeles, CA: Semiotexte, pp. 170–192.

It is important to grasp the importance of structuralism for design practices, not so much for what it is itself but for its relation to narratology and to other cultural practices, as well as for the thinking that developed, more or less simultaneously, under the heading of poststructuralism.

French structuralism was inaugurated in the 1950s by the cultural anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, who analysed, using Saussure’s linguistic model, such cultural phenomena as mythology, kinship relations, and food preparation. In its early form, in the 1950s and 1960s, structuralism cut across the traditional disciplinary boundaries of the humanities and social sciences by claiming to provide an objective account of all social and cultural practices. It views cultural practices as combinations of signs that have a set significance, perhaps, more clearly, a dominant interpretation, for the members of a particular culture. It undertakes to make explicit the rules and procedures by which the practices have achieved their cultural significance. In addition, it seeks to specify what that significance is, by reference to an underlying system of the relationships among signifying elements and their rules of combination (Abrams, 1999: 300).

The structuralist impulse was little understood in Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-American academic cultures, where structure was considered as the complement to function within a structural-functionalist paradigm. Hence structure was seen as an element in the functionalism that dominated and continues to dominate those cultures. This is particularly the case in design practices because, as Burkhardt (1988: 146) notes, “The birth of design is bound up with the birth of functionalism.”

The importance of structuralism, however, is not as a form of reductionism, i.e. the notion that all appearances or surface structures can be reduced to a few structural elements, but rather as a form of relational thinking. As such, structuralism serves, on the one hand, as a critique of positivism i.e. a critique of the view that the world consists of fully-formed entities with predefined properties. On the other hand, it serves as a critique of functionalism, i.e. a critique of the view that an act is originary and is a simple cause which gives rise to a simple effect.

Structuralism opens up thought to the potential of network ontologies, that is, non-positivistic modes of existence, and network ‘causalities’, that is, forms of non-originary, co-implicated inter-action.

Structuralism, the Death of God and Post-Humanism

Deleuze (2004: 175) notes that one consequence of the structuralist emphasis on symbolic elements that primarily do not have extrinsic designation nor intrinsic signification but rather a positional, relational sense,

“is that structuralism is inseparable from a new materialism, a new atheism, a new anti-humanism. For if the place is primary in relation to whatever occupies it, it certainly will not do to replace God with man in order to change the structure. And if this place is the dummy-hand [la place du mort, i.e. the dead man’s place], the death of God surely means the death of man as well, in favor, we hope, of something yet to come, but which could only come within the structure and through its mutation.”

(Deleuze, 2004: 175)

Three types of relation can be distinguished, Deleuze (2004: 176) explains, real, imaginary and symbolic, of which it is the third which is of key significance for structuralism. The first type is established between elements which enjoy independence or autonomy. He gives the examples of 3 + 2 or 2/3. The elements are real and such relations must themselves be said to be real. The second type of relationship is established between terms for which the value is not specified but which, in each case, must have a determined value. He gives the example of x2 + y2 – R2 = 0. Such relations can be called imaginary. The third type is established between elements which have no determined value themselves, and which nevertheless determine each other reciprocally in the relation. His example is ydy + xdx = 0, or dy-/ dx = – x/y. Such relationships are symbolic, and the corresponding elements are held in a differential relationship: dy is totally undetermined in relation to y, and dx is totally undetermined in relation to x. Each one has neither existence, value, nor signification. Yet the relation dy/dx is totally determined. The two elements determine each other reciprocally in the relation. This process of a reciprocal determination is at the heart of a relationship that allows one to define the symbolic nature.

Deleuze (2004: 177) continues: Corresponding to the determination of differential relations are singularities. These are distributions of singular points which characterise curves or figures. For example, a triangle has three singular points. Thus, Deleuze argues, the notion of singularity becomes crucial. Taken literally, it seems to belong to all domains in which there is structure. The general formula which serves as a manifesto for structuralism, i.e. that “to think is to cast a throw of the dice,” itself refers to the singularities represented by the sharply outlined points on the dice. Every structure, then presents two aspects: a system of differential relations according to which the symbolic elements determine themselves reciprocally; and a system of singularities corresponding to these relations and tracing the space of the structure. Every structure, Deleuze concludes, is a multiplicity.

Significant for the understanding of the role of designed objects, artefacts and other design interventions, Deleuze explains that, “Symbolic elements are incarnated in the real beings and objects of the domain considered; the differential relations are actualized in real relations between these beings; the singularities are so many places in the structure, which distributes the imaginary attitudes or roles of the beings or objects that come to occupy them.”

In a certain sense, then, structures are not actual. What is actual is that in which the structure is incarnated or rather what the structure constitutes when it is incarnated. However, in itself, a structure is neither actual nor fictional, neither real nor possible (Deleuze, 2004: 178). Deleuze suggests that the word virtuality might designate the mode of the structure or the object of theory. However, he cautions that this would have to be on the condition that we eliminate any vagueness about virtuality. The virtual has a reality which is proper to it, but which does not merge with any actual reality, any present or past actuality. It could be said of structure that it is real without being actual, ideal without being abstract, a sort of ideal reservoir or repertoire, in which everything coexists virtually, but where the actualisation is necessarily carried out according to exclusive rules, always implicating partial combinations and unconscious choices.

Structuralism and narratology

The word ‘narratology’ was first used by the Franco-Bulgarian philosopher Tzvetan Todorov and has since made remarkable progress due to the works of such narratologists as Claude Bremond, A. J. Greimas, Roland Barthes, and Gerard Genette. It derived from Vladimir Propp’s study of Russian forktales and the structuralism of Claude Lévi-Strauss, who had re-evaluated the Russian formalism of the 1910s to the 1930s.

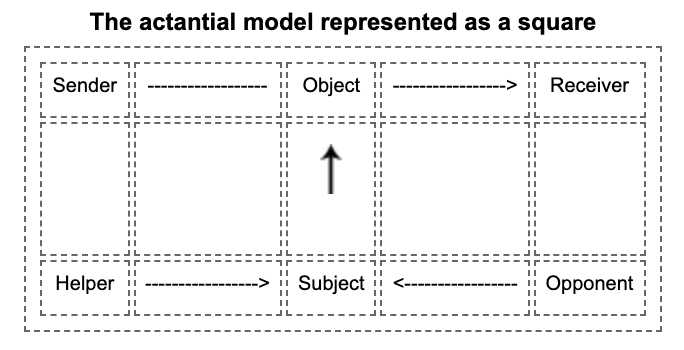

A. J. Greimas, a linguist and semiotician, considered Propp’s morphology in connection with Lévi-Strauss’s structural analysis of myth. Through a consideration of Propp’s thirty-one functions, Greimas defined an actant as a fundamental role at the level of narrative deep structure. Greimas’ actantial model schematically shows the functions and roles that characters perform in a narrative. Greimas replaced Propp’s syntagmatic structure of narrative with a paradigmatic one: the establishment of the actors by the description of the functions and the reduction of the classification of actors to actants of the genre (Susumu, 2010).

Greimas also employed Souriau’s catalogue of dramatic function. In so doing, Greimas found that the actantial interpretation could be applied to different kinds of narrative, not just folktale, and that Souriau’s results could be compared with those of Propp.

In this way, Greimas arrived at his first actantial model:

Structuralism outside narratology

A good example of how structuralist thought, as relational thinking or the thinking of difference, is valuable outside of the domain of narratology can be found in Rosalind Krauss’ (1979) discussion of sculpture in what she calls the expanded field.

References

Abrams, M.H. (1999). A Glossary of Literary Terms, 7th ed. Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle.

Burkhardt, F. (1988). Design and ‘avant-postmodernism’. In: Design after modernism, edited by J. Thakara. London, UK: Thames and Hudson, 145–151.

Deleuze, G. (2004) How do we recognise structuralism?, in McMahon, M. and Stivale, C. (trans.) Desert Islands and Other Texts 1953–74. Los Angeles, CA: Semiotexte, pp. 170–192.

Krauss, R. E. (1979) ‘Sculpture in the expanded field’, October, 8, pp. 30–44. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/778224 (Accessed: 10 February 2016).

Susumu, O. (2010). Greimas’s actantial model and the Cinderella Story: the simplest way for the structural analysis of narratives [Thesis]. Hirosaki, Japan: Hirosaki University. Available from http://repository.ul.hirosaki-u.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/10129/3788/1/JinbunShakaiRonso_J24_L13.pdf [Accessed 2 February 2016]