RELATED TERMS: Body; Khora or Chora; Phenomenology; Time

Place

Places are events; they ‘take place’ over extended periods of time. Places are sensible, perceivable by the senses, and intelligible, existing in thought, in the imagination and in the memory. They also constitute a third order, khôra or chora, an interval between the sensible and the intelligible. Such an interval, it is contended, permits or enables designs to ‘take place’ as neither simply sensible nor intelligible, thus allowing for the in-vention, the in-coming of the other: a ‘being-with’, a sharing, rather than a self-contained or discrete ‘being’ or a self-possessed identity. That is to say, while designs are pre-conceived in terms of intention and telos, they may exceed that conception, potentially opening to (a new, radical) inception in the ways in which they continue to act and be acted upon in the world. In their end (telos), so to speak, is their beginning (in praxis).

‘Place’ institutes a complicated, multi-perspectival, dialogical phenomenology.

From the perspective of design practices, place is intimately related to bodily forms and to the differentiations, according to the deictic, associative and affective orientations and horizons of bodies, among ‘my’ places, ‘your’ places, ‘our’ places and ‘their’ places, all of which form complex topological spaces, whose boundaries are often marked by designed artefacts and environments.

As Cecena Alvarez (2015) notes, “A place is not a portion of space. Place is the lived expression of the spatial apprehension of reality.”

Placiality

While design practices may often take spatiality into account, it could be said that they are equally, if not more, concerned with ‘place’ than ‘space’; as, indeed, it may be said that they are equally, if not more, concerned with ‘historicity’ than temporality, since ‘placiality’ and ‘historicity’ are more concrete than the more abstract ‘spatiality’ and ‘temporality’.

As Stephen Hardy comments, ‘placiality’ and the adjective ‘placial’, from which the substantive is derived, are not words which appear in many dictionaries of the English language, even though ‘spatiality’ and ‘spatial’ are common enough usages.

Some of the reasons for this disparity, Hardy indicates, are explained in Edward Casey’s (1997) book, The Fate of Place. Casey introduces the terms ‘placial’ and ‘placiality’ in the course of examining the ways in which ‘space’ has come to dominate philosophical thinking, despite an abiding concern with matters of ‘place’.

The crux of Casey’s argument is that Western philosophising from the time of Plato up to, and partly including, Kant found itself caught up in thinking increasingly abstractly about that in which we are immersed and that by which we are surrounded.

The ‘rediscovery’, so to speak, of place, Casey argues, begins with Kant, although his thinking is divided on the matter. On the one hand, Kant, in his Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science, reduces place to nothing more than a point in space. However, on the other hand, in his essay, Concerning the Ultimate Ground of the Differentiation of Regions in Space, he provides the beginnings for a modern philosophising of the significance of ‘place’ as opposed to the measurement of a supremely abstracted ‘space’.

Kant’s crucial development in this essay is to consider the importance of the human body and the way it is organised and orientated, Casey explains.

Casey further argues that insights of this kind were not fully taken up in European philosophising until the beginning of the 20th century when the phenomenology of Husserl begins to explore more fully the relation of the physical situation of the human body to the organisation of its perceptions. Husserl’s philosophical descendants, including Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, Deleuze and others, further develop this exploration.

Jason Cons (2016) brings to attention the importance of what he calls the ‘placial imagination’ when he notes that,

“I am headed home to Austin, TX — to “my” place. When I arrive there, family, work, friends, and sets of familiar patterns and obligations will quickly reintegrate me into a spatiality that I know well. These patter[n]s are one aspect of a broader set of perceptions and situations that constitute my own intimate experience of place and my relationship to broader currents and flows of work in contemporary academia and social life in a rapidly growing city.”

In this context, one might talk of ‘spatial flows’ and ‘placial knots’ or placial entanglements, the latter two terms evoking where flows intersect and become significant for particular individuals.

Space

Space is abstract, in contrast to place, which is concrete. Nevertheless, both space and place are capable of acting in designed artefacts, services and environments. That is, place and space become actants.

One key issue for the concept of space in spatial design, including the design of narrative environments, is the back-and-forth conversion of Euclidean space and topological space. This is to recognise, deriving an insight from Gilles Simondon (2020), that a ‘place’, as a living entity or an entity for living, does not only have an absolute interiority and absolute exteriority, marking its boundary limits, so to speak, but is also mediated by a chain of intermediary interiorities and exteriorities, topological folds. A spatial design unfolds according to topological structurations, weaving together interiors and exteriors, which convert Euclidean into topological space. It is through these topological structurations that narratives are further woven into the spatial design.

A location or a site might be said to be a space that does not have placeness or placiality. In other words, it has Euclidean dimensions but no topological ‘twists’ with which to engage.

Stewart, Gapenne and Di Paolo (2010: ix) argue that,

“we put the world together in a spatial sense through movement and do so from the very beginning of our lives. Spatial concepts are born in kinesthesia and in our correlative capacity to think in movement. Accordingly, the constitution of space begins not with adult thoughts about space but in infant experience.”

Futhermore, they state that, “the constitution of a “kinesthetic function”, itself rooted in proprioception, is foundational for the emergence of the prereflective experience of spatiality and distal objects.”

Space may then be discussed as a becoming, a spacing, for example, hodological space as the becoming of a defined path; Euclidean spacing as a becoming of geometrical, dimensional relation; Cartesian spacing as an algebrisation of the geometry of Euclidean dimensions; topological spacing as a relation between the hodological and the Euclidean, complicating the near and the far; bodily spacing as interiorisation, exteriorisation, the exteriorisation of interior spacing and the interiorisation of exterior spacing.

For design practices, it is important to note that the moving body, the kinaesthetic body in motion, is configured alongside the acting body with its various sensuous, aesthetic and pragmatic orientations, the body which, through its movements, acts upon others and upon the material world. Designs are configured to address both motion-motility and aesthesis-action.

Discussion:

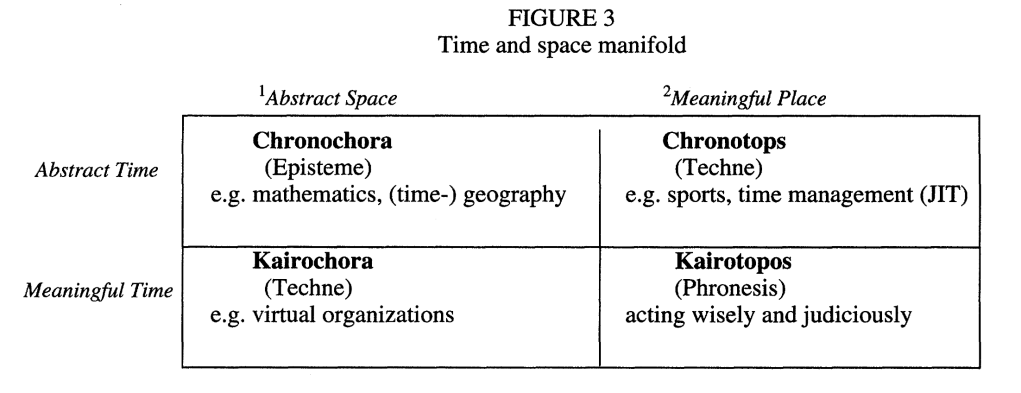

How useful might the ancient Greek notions for place, chora and topos, be alongside the two ancient Greek conceptions of time, kairos and chronos, in developing an understanding of how time and space can be configured in designed entities of whatever character, moving from the relatively abstract to the more experientially meaningful? Perhaps Hans Ramo’s (1999) diagram might be of value on this context:

In this case, designed entities might be considered to be concerned with the creation of a ‘kairotopos’ as a place of meaningful time and meaningful space, where one might learn to develop ‘phronesis’ or ‘practical wisdom’.

Space as Actant

A space can be defined as an actor [actant] embodied in the virtual or physical built environment, and therefore exerting a presence that can be defined in terms of a spatial analysis of light, volume, obstacles and flow routines, amongst others, which themselves give rise to certain affordances or possibilities for other ‘actants’, including people.

Place, Locality, Design

One difficulty for any contemporary discussion of place concerns the dynamics between place as gathering location for a localised community and the commercial forces of different scales which cut across any such place, potentially leading to community fragmentation and division. One example in the context of the UK is the role of the high-profile football club as marker of place. Wilczyńska (2022) notes that,

“For many people, supporting a football club is a lifelong experience. Loyalty, constancy, attachment to place and rituals are basic values in the football fandoms, which is exceptional in the time of liquid modernity (Bauman 2000). Footballers, coaches, and club officials change, but the fans remain faithful.”

However, as Jonathan Wilson (2024) comments, while there has always been a tension between the idea of the football club as an idealised symbol of place and the commercial reality, this tension has never been felt more acutely than it does in the 2020s.

The tension exhibited in the case of football clubs brings to attention the awareness that, just as the notion of ‘place’ is problematic, so is that of ‘local’. There is little doubt that, in the UK, the presence of local, independent businesses is taken as an indicator of the presence of desirable values such as, for example, community, shared perspectives, wealth, quality and sustainability. The question remains, however, of how local can such businesses be in the 21st century, given the interpenetration of localisation and economic globalisation (Baggini, 2024).

In the weakest sense, Baggini notes, anything that exists in a particular locality can be deemed local. A second, stronger sense is that of a local economy where business owners and employees live in the community and money circulates largely within a locality of, say, a 30-mile radius. In a third, alternative sense, such a strictly geographical understanding of local does not necessarily match the values of consumers for whom what matters is not so much that trade is local but that it is between small, independent parties, wherever they are located, offering fairly-traded products. This model, while advocating local-to-local fair trade, may in fact be trans-national in geographical extent.

In addition to such economic considerations are the perceived environmental benefits of the local. These benefits are not, however, straightforward. For example, fewer food miles ought to mean a smaller carbon footprint. However, this is not necessarily the case. Studies show that many imported foods, for example, lettuces grown in Spain during the British winter, have a lower carbon footprint than local alternatives, depending on how and where they were grown.

The economic and environmental values of local businesses have been supplemented in recent years by their value in creating a sense of community and cohesion, a role that has fallen disproportionately on their shoulders in the absence of other factors holding neighbourhoods together. Decades of gradual socio-cultural individualisation have led, as the 2016 European Quality of Life Survey showed, to a situation where, in response to a question asking respondents whether they felt close to others in the area where they lived, the UK ranked 20th out of 28 among European Union countries.

For many academics and activists, such social, economic and environmental factors are key elements of sustainability, with social cohesion of central importance in buoying the economy and preventing environmental decay.

In relation to design, such processes of commodification of products and produce, which concerns where and how they are produced and exchanged, and individualisation of personhood, which concerns how such products and produce are purchased and consumed, in relation to how they, at the same time, support identities, are of great significance.

While many of the commodities discussed in the context of a local economy are related to food and agriculture, nevertheless, the questions for design are not simply about the products themselves. In as far as they concern the processes of commodification and individualisation, the questions are also about design of societies, design of communities, design of economies, design of ecologies and design of environments; and, indeed, design of societies and communities in relation to economies, ecologies and environments, as inter-related aspects of what might be considered to be single phenomenon: the ways in which designs of different orders and characteristics affect the flows and balances of localisation-globalisation as a spatio-temporal field and a socio-historical reality.

References

Baggini, J. (2024) What does ‘local’ actually mean?, Financial Times, 30 March, House & Home section, 1-2.

Casey, E. (1997). The Fate of place: a philosophical history. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Cecena Alvarez, R. (2015). Phenomenology and deixis. The deictic constitution of the world within an ek-sistential frame of reference. In: Germanos, D., and Liapi, M., eds. Digital Proceedings of the Symposium with International Participation: Places for Learning Experiences. Think, Make, Change (Thessaloniki, Greece, 09-10 January 2015). Athens, Greece: Greek National Documentation Centre.

Cons, J. (2016). Conclusion: the placial imagination. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 6 (4), 788–789. Available from http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13412-015-0262-8 [Accessed 29 August 2019].

Hardy, S. (2000). Placiality: The renewal of the significance of place in modern cultural theory. Brno Studies in English, 26, 85–100. Available from https://digilib.phil.muni.cz/bitstream/handle/11222.digilib/104271/1_BrnoStudiesEnglish_26-2000-1_8.pdf?sequence=1%5BAccessed 29 August 2019].

Ramo, H. (1999) ‘An Aristotelian human time-space manifold: from chronochora to kairotopos’, Time & Society, 8(2–3), pp. 309–328. doi: 10.1177/0961463X99008002006.

Sallis, J. (1999) Chorology: beginning in Plato’s Timaeus. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Simondon, G. (2020) Individuation in light of notions of form and information. Translated by T. Adkins. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Stewart, J., Gapenne, O. and Di Paolo, E. A. (eds) (2010) Enaction: toward a new paradigm for cognitive science. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Wilczyńska, B. (2022) ‘Being a Yid’: Jewish Identity of Tottenham Hotspur Fans – analysis and interpretation’, Qualitative Sociology Review, 18(3), pp. 86–105. doi: 10.18778/1733-8077.18.3.04.

Wilson, J. (2024) Postecoglou the ‘plastic’ manager is the perfect fit for a club at odds with its fans. Observer, 28 April, Sport section, p.20.

Further Reading

Malpas, J. (2006) Heidegger’s topology: Being, place, world. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.