RELATED TERMS: Affordances; Avant-garde movements; Critical Theory; Critical thinking; Cultural Studies; Dissensus – Ranciere; Ethnomethodology; Feminism and Materialism; Historical materialism – Marxism; Multimodal research; Ontology; Performance and Performativity; Postmodernism; Poststructuralism; Psychogeography; Research Methodologies; Storyworld; Theoretical Practice; Wicked Problems – Wicked Challenges

“philosophers and literary theorists frequently refer to theories as stories (in this story we have to accept that … ). Or even scenarios. It is as if phiction and filosophy had changed places.” (Brooke-Rose, 1991: 19)

“Deconstruction is neither a theory nor a philosophy. It is neither a school nor a method. It is not even a discourse, nor an act, nor a practice. It is what happens, what is happening today in what they call society, politics, diplomacy, economics, historical reality, and so on and so forth.” (Derrida, 1990: 85)

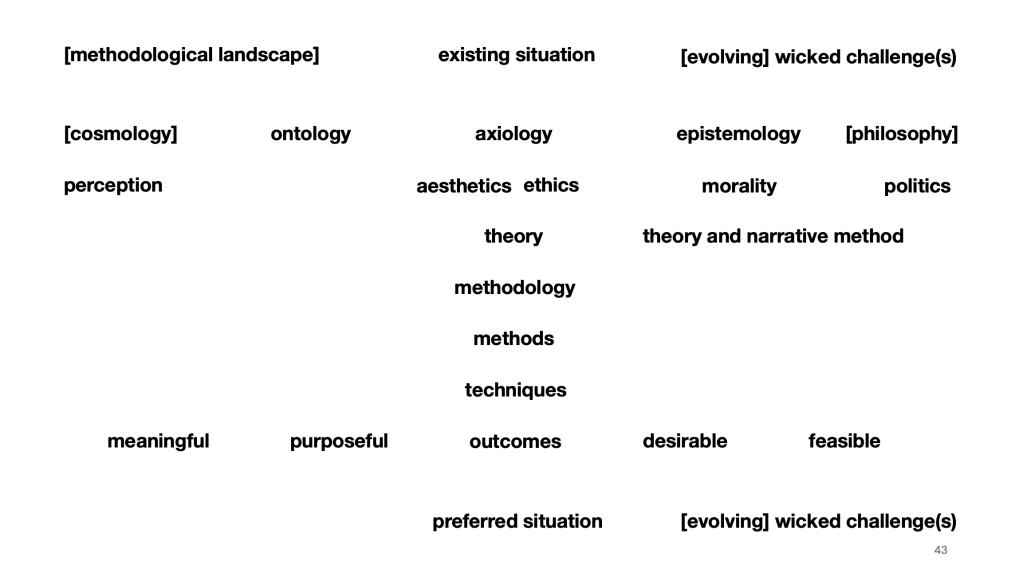

The design of narrative environments, as an example of a contemporary design practice, is research-based and may also be research-led. Indeed, it may even serve as an example of design-led research. In short, design and research are closely intertwined in many contemporary design practices. This is to acknowledge, along with Smith and Dean (2009: 1), the potentially close relationship between research and creative practice: creative practice can impact academic research positively while academic research can have a reciprocal impact on creative practice. The following text discusses the inter-relationships of theoretical perspectives, methodologies and methods to the epistemological, ontological and axiological – that is, philosophical or cosmological – presuppositions they assume, from the perspective of design practice and design education and its pedagogical principles.

In conducting research, a methodology guides the orientation of the research and frames the research question. Once these are decided, specific research methods are selected which generate the evidence, or the material outputs of practice in the case of practice-based research, to address the research question and/or the design challenge.

A methodology is a system of methods, principles and theories used in a particular discipline. It is akin to a philosophy or an approach which holds the methods and theories together as a coherent system. More narrowly, the term methodology may refer to the branch of philosophy concerned with the science of method.

A method a way of proceeding or doing something, i.e. a procedure, especially one that is systematic or regular; orderliness of thought or action. As methods, it refers to the techniques or arrangement of work for a particular field or subject.

In practice, matters are far less clear-cut than this division suggests. Adherence to a methodology both enables research to proceed but also limits research by establishing boundaries of what it is permissible to see, to say and to argue. It is this adherence which, if it become too rigid or mechanistic, gives some research its ‘artificial’ or ‘limited’ feel; or limits its field of application or relevance. All research, to some extent, has to deal with mismatches between methods and methodology and with the limits imposed by a methodology and its associated methods.

A methodology, in order to proceed, requires certain ontological assumptions about what already exists, how it exists and how new existents may be discovered, as well as certain epistemological assumptions about what is already known, how it is known and how new knowledge can be produced. It also makes certain axiological assumptions about what is valuable, how it is valued and how that value should be sustained or enhanced. These assumptions, as decisions, may not be wholly explicit in the methodology until it is thoroughly questioned.

Key Terms

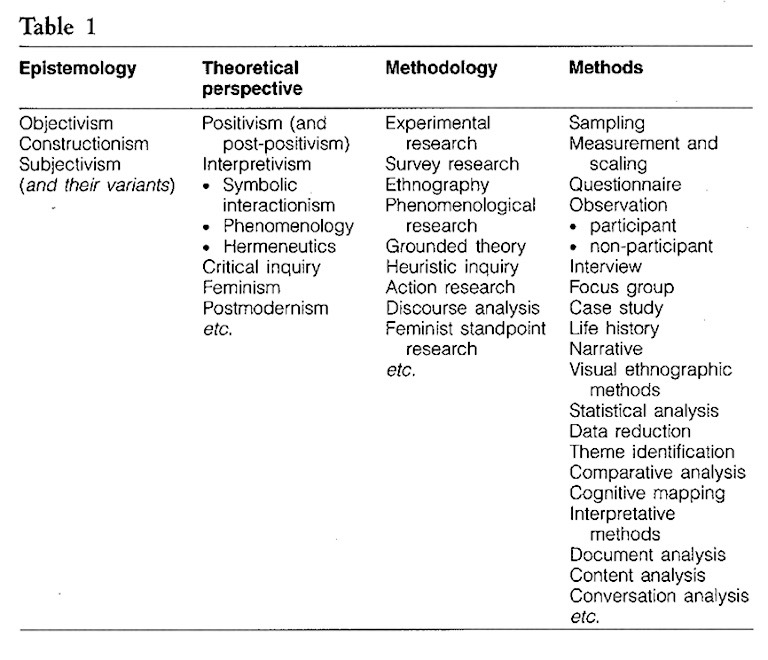

Michael Crotty (1998) suggests that when conducting research we find ourselves facing four questions:

- What methods do we propose to use?

- What methodology governs our choice and use of methods?

- What theoretical perspective lies behind the methodology in question?

- What epistemology informs this theoretical perspective?

Methods are the techniques or procedures used to gather and analyse data related to some research question or hypothesis.

Crotty notes that, the distinction between qualitative research and quantitative research occurs at the level of methods, not at the level of epistemology or theoretical perspective.

Methodology is the strategy, plan of action, process or design lying behind the choice and use of particular methods and linking the choice and use of methods to the desired outcomes.This brings to attention the fact that research is oriented towards outcomes, both practical and theoretical: to create new knowledge and to orient practical, design interventions.

Theoretical perspective is the philosophical stance informing the methodology and thus providing a context for the process and grounding its logic and criteria.

Hay (2002), as cited by Olsson and Jerneck (2018) notes that,

“Theory can be descriptive, prescriptive, or predictive and can be used to challenge or confirm stated and unstated assumptions. Theories are characterized by their distinct perspectives and are (often) conceived of and expressed to represent, or even consolidate, a special subject-position or vantage point”.

Epistemology is the theory of knowledge embedded in the theoretical perspective and thereby in the methodology. On a practical level, the question of epistemology translates into contentious issues regarding research methodologies.

Helen Verran (2018) proposes that the ‘modern’ knower, or the subject who is supposed to know, the knower under the conditions of ‘modernity’ or the ‘scientific’ knower, is a removed, judging observer. This scenario assumes a subject facing an object. It is ‘objective’ in that sense. For example, the modern knower is like a modern ‘critic’: a reader who perceives and comments on an ‘object-text’. The pre- and post-modern knower, on the contrary, is a situated, entangled subject, entangled with the object, unable to separate the object entirely from the subject. In this way, the figure of the knower is dissolved into the epistemic practices, ways of ‘knowing-how’, that establish the ‘here’ and the ‘now’, the ‘present and ‘absent’, the ‘positive’ and the ‘negative’, the ‘visible’ and the ‘invisible’. The modern knower might also be said to be singular, an individual ‘brain’ or ‘consciousness’), while pre- and post-modern knowers are collective, social, working together within the horizons of given epistemic practices.

Gormley (2005) makes a similar point. He cites the Principia Cybernetica Web which argues that a clear trend can be discerned in the history of epistemology. The earliest theories of knowledge stressed its absolute, permanent character. Later theories placed the emphasis on the relativity or situation-dependence of knowledge; its continuous development or evolution; and its active interference with the world and its subjects and objects. The overall trend marks a move from a static, passive view of knowledge toward a more adaptive and active one.

Ontology is the study of being. It is concerned with ‘what is’, with the nature of existence, with the structure of reality as such. It sits alongside epistemology in informing the theoretical perspective, because each theoretical perspective embodies a certain way of understanding what is (ontology) as well as a certain way of understanding what it means to know (epistemology) about what exists, defining the relationship between the knower and the known in the real.

Crotty provides the following table, by way of example, showing how this group of terms are inter-related conceptually:

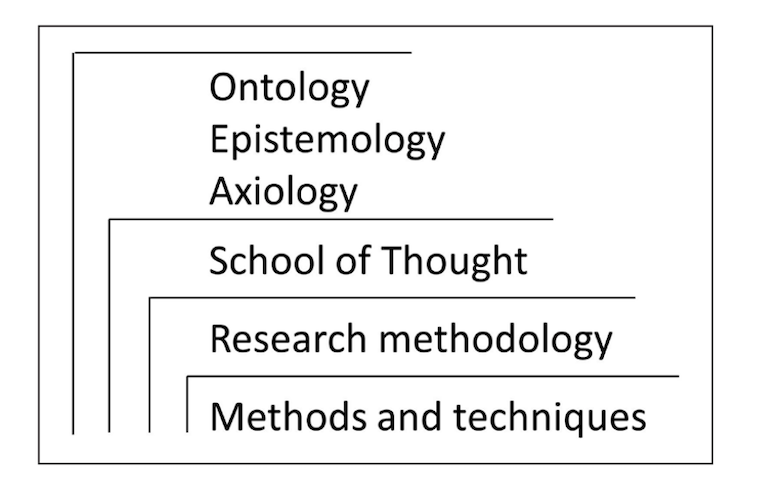

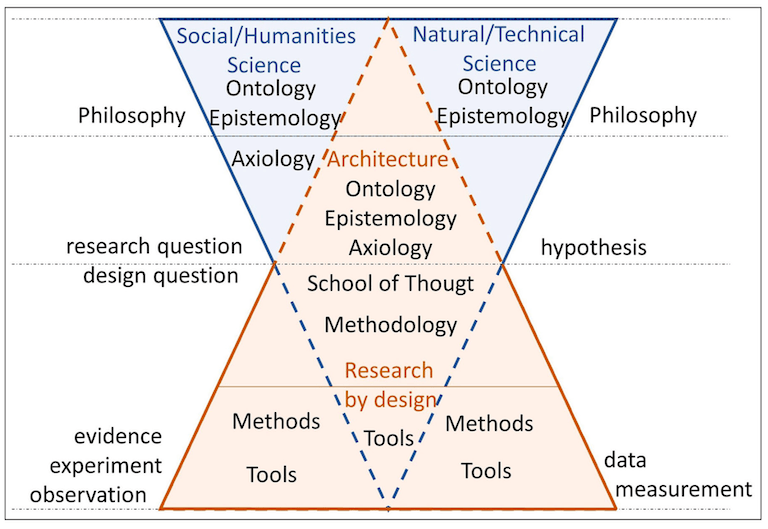

Krystyna Pietrzyk (2022) explains that a research paradigm, or worldview, or in Crotty’s terms ‘theoretical perspective’, can be described as the set of common beliefs and agreements shared among researchers about how specific challenges should be understood and addressed. It can be shown as a hierarchical system of inquiry as follows:

This is modified from Groat and Wang (2013). For Pietrzyk, a philosophical, that is, an ontological, epistemological and axiological, perspective on a research challenge guides the researcher through the variety of methodological approaches, methods and tools. The methods and techniques at the disposal of the researcher, in other words, are subordinate to considerations of purpose and philosophy.

What Pietrzyk adds to Crotty is the inclusion of axiology to ontology and epistemology. Axiology, as a study of the nature of values and valuation, is a complementary part of the system of inquiry. Axiology, relevant in humanities and social research, is added to the axiology and epistemology present in the natural and technical sciences, because values such as well-being, environmental safety, generational equality, social justice or participation can guide design research when working on wicked challenges, for example, those related to sustainable development.

Piterzyk diagrams this set of relations as follows:

References

Brooke-Rose, C. (1991) Whatever happened to narratology?, in Stories, theories and things. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 16–27.

Crotty, M. J. (1998) The Foundations of social research: Meaning and perspective in the research process. London, UK: Sage Publications.

Derrida, J. (1990). Some statements and truisms about neologisms, newisms, postisms, parasitisms, and other small seismisms. In: The States of ‘Theory’: history, art, and critical discourse. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 63–94.

D’Oro, G. and Overgaard, S. (eds) (2017) Cambridge companion to philosophical methodology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Gormley, L. (2005) Some Insights for Comparative Education Researchers from the Anti-racist Education Discourse on Epistemology, Ontology, and Axiology’, in Dei, G. J. S. and Johal, G. S. (eds) Critical issues in Anti-Racist Research Methodologies. New York, NY: Peter Lang, pp. 95–123.

Groat, L. and Wang, D. (2013) Architectural Research Methods. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

Hay, C. (2002) Political analysis: a critical introduction. Houndmills, Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave.

Joost, G. et al. (eds) (2016) Design as research: Positions, arguments, perspectives. Basel, CH: Birkhäuser.

Olsson, L. and Jerneck, A. (2018) Social fields and natural systems: Integrating knowledge about society and nature, Ecology and Society, 23(3). doi: 10.5751/ES-10333-230326.

Pietrzyk, K. (2022) Wicked problems in architectural research: The Role of research by design’, ARENA Journal of Architectural Research, 7(1), pp. 1–16. doi: 10.5334/ajar.296.

Smith, H. and Dean, R. T. (2009) Practice-led research, research-led practice in the creative arts. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press.

Verran, H. (2018) The Politics of working cosmologies together while keeping them separate, in de la Cadena, M. and Blaser, M. (eds) A World of many worlds. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, pp. 112–130.