RELATED TERMS: Dasein; Technology, Writing, Design; Libidinal Economy – Part 1;

Before-After-Thought

In James Joyce’s terms, thrownness, or living in the wake, is expressed as,

“from the night we are and feel and fade with to the yesterselves we tread to turnupon” (FW473. I0-11, quoted by Heath,1984).

Design Projection

In relation to the potential of design practices, what is proposed here, through a consideration of the German word entwurf as it is used in Heidegger[1] and subsequent writers, is that:

first, designing can ‘throw open’, through inquiry;

second, designing can ‘throw-ahead’ as projection;

third, (completed) designs can continue to throw ahead and cast backwards through material and semiotic persistence and adaptation; and

fourth, designing and designs can ‘un-throw’ or ‘throw off’ what has already been thrown or, in other words, designing and designs can ‘over-throw’ and/or ‘re-throw’, through re-interpretation, re-making and re-contextualisation.

In short, designing and designs can ‘project’ in a process of prolonged retrojective-projective un-making, re-making and un-re-making [within a horizon of worlding (as) ending the world (as) affirmative engaging with worldlessness-designlessness].

In the words of Gary Shteyngart (2022), who sees the comedic potential of this condition of ‘being thrown’ or ‘thrownness’,

“We are all small individuals kicked ass-first on to the stage of history, given terrible lines and worse costumes…”

Design is a realm of thrownness, the givenness of the ‘there’ of the world, and thrown-openness, co-extensive with the human condition: materialised interpretations developed on the basis of inquiry into need and desire. Human action is thereby defined as, in some sense or other, ‘designing’: throwing-off, over-throwing, projecting, un-throwing a prior projection.

For Elif Shafak (2025), for example, writing was the means she used to ‘overthrow’, or ‘transcend’ as she puts it, the circumstances into which she was thrown (born). She says,

“Constantly talking to imaginary characters, I started making up stories to transcend the little box I was put into [that is, the gender roles and conservative expectations of life for a woman in Ankara, Turkey], to dismantle those walls and see what was beyond.”

Writing here can be understood as both a metaphor for designing, as a practice of configuring symbolic, semiotic means (language as materiality), and as a literal means of re-configuring the self, a practice by means of which the self can be re-configured and the self-situation relationship re-designed: designing, through action, crafting an alternative narrative (for a women’s life) environment (in another country).

[Aside: The ‘deconstructive’ aspect of this un- or over-throwing should not be overlooked here. Such un-throwing does not constitute a clean break. If it represents a kind of ‘freedom’, it is one that is constrained by the initial situation. One can never be wholly or completely ‘free’, if this term seems to imply ‘contextlessness’ or ‘situationlessness’. As an ongoing process, un-throwing (designing, re-designing or un-designing) carries along with it traces of that from which the ‘overcoming’ or ‘transcendence’ is sought; indeed, the un-throwing process, as concrete struggle, is firmly shaped by the initial thrown situation and the opportunities, or lack of opportunities, it affords. For example, as Matthew Jenny (2025) notes, “if we want to create new stories of fatherhood, we first have to acknowledge and debunk its foundational myths.”

The self, even if existing within a novel narrative environmental configuration, remains troubled by the (hi)story, the place and the expectations (futurity) into which one was initially ‘thrown’. The degree or intensity of that troubling-struggle, the degree of one’s (dis)functionality, depends on the degree to which one initially accepted or was immersed in the initial horizons of the field of interplay, and continues to accept or be immersed in them, even if not consciously. It is here that what might be deemed a ‘symptom’ of a pathology in one situation comes to be seen as an element in a libidinal economy, wherein that same ‘symptom’, instead of fixing and entrapping in repetition, opens to enjoyment, release and difference, albeit in a complex way and not simply as ‘freedom’ or ‘autonomy’.]

In Heidegger, Sheehan (2015: xv) explains, thrownness is Geworfenheit; thrown-openness is der geworfene Entwurf; the thrown-open realm is der Entwurfbereich, the world as thrown, as ‘designed’. Heidegger uses the German word Entwurf to indicate the way in which the possibilities we press toward are always already ‘projected’ ahead. As the translators of Being and Time note, Entwurf could readily have been translated as ‘design.’ Indeed Entwurf contains the same etymological elements as the English word design: throwing off or throwing away from one (Heidegger, 1962, fn 1, p. 185).

The process of being carried away into the realm of possibility and returning to oneself in actuality, thereby opening a discursive space, is referred to by Heidegger as the world, or alternatively as the clearing or the open. Heidegger says that to ex-sist could be more adequately translated as ‘sustaining a realm of openness’, in other words, sustaining a world (of actuality as concretised possibility). The turning back or returning to our here-and-now selves, away from the possibility that we are, is also a turning back to the things we currently encounter as we render them meaningfully present in terms of specific possibilities (Sheehan, 2015: 103).

In 1930, Heidegger interpreted this movement of being thrown-ahead-and-returning in terms of existential thrown-openness or thrown projectedness, geworfener Entwurf. It is this movement that makes possible the existentiel synthesising of things with possible meanings (Sheehan, 2015: 103).

This existential projection stretches us apart from ourselves, giving us an extended quality, taking us away into the possible. We do not lose ourselves there. Rather the possible, as the rendering-possible of the actual, is enabled to speak back precisely upon ourselves as projection, as a uniting and binding synthesis (Sheehan, 2015: 104).

From this existential movement, there follow existentiel acts of making sense of things, for example, by way of the apophantic (assertive) ‘as’ of declarative sentences or the hermeneutical ‘as’ of practical activity. Our constantly operative existential identity as stretched-ahead defines our being present to ourselves as living ahead in possibilities. It is this which makes possible the discursive ‘as’ whereby we understand what and how things currently are. Thus, the thrown-openness that is our very being, is also that occurrence in which the thing we problematise as the as-structure has its origin (Sheehan, 2015: 104).

For Heidegger, our lived environment is not just a natural encircling ring of instinctual drives that befits an animal, but an open-ended ‘as-structured’ world of possible meanings that we can discuss, disagree over and choose among (Sheehan, 2015: 104). The entailment of our existential thrown-openness is that we can and must make sense of whatever confronts us (Sheehan, 2015: 105).

In this context, the process of designing and of using designed phenomenal entities, as a process of being thrown-ahead-and-returning to ourselves, is not a foreclosure of possibilities around a predetermined end, for example, a specific function. Rather, it is a throwing off or casting off, a throwing ahead, a projection, that opens up worlds of possibilities against which we judge and seek to modify our actuality.

In later writings, the notion of ‘the appropriated clearing’ or appropriation (Ereignis) is Heidegger’s re-inscription of what he had earlier called thrownness (Geworfenheit) or thrown-openness (der geworfener Entwurf). The human being, as thrown-open or appropriated, is the open space or clearing within which the meaningful presence of things can occur. For Sheehan (2015: xv), this previous sentence is Heidegger’s philosophy in a nutshell. In some sense, this defines his phenomenology of world and worldliness.

Aicher on entwurf

Aicher (2015: 75) points out that in English design was originally the equivalent of the German word ‘entwurf’, a word that means a draft, the development of a new object or a new thing. Aicher (2015: 148) elaborates [lower case in the original]:

“the german word entwurf (design) comes from werfen (to throw), and so implies that design is concerned with throwing something out from oneself [projecting something]. in the same way that you throw out a line. the word catches the idea pretty precisely. you throw something up in the air to see how it behaves.”

Flusser on entwurf

Heidegger emphasizes the lack of choice about the point from which our understanding begins when he argues that, as being, Dasein is something that has been thrown. It has been brought into its ‘there’, but not of its own accord (Heidegger, 1962: 329).

For Heidegger, the movement or momentum which such a ‘throw’ implies does not come to a stop because Dasein now is there, so to speak, having arrived at a destination. Dasein continues to be pulled along along in thrownness. In short, as something which has been thrown into the world, Dasein loses itself in the world in its submission to that with which it is to concern itself, its facticity as embroiled in matters of concern (Heidegger, 1962: 400).

Flusser suggests that Heidegger uses the German word Entwurf, which can be translated as design, project or outline, in a new sense. Flusser contends that this usage allows us henceforth to invert our being-thrown-into-the-world, allowing us to pro-ject ourselves upon the world (Hanke, 2016).

It is for this reason that we can then speak of design practices as the endeavour to throw-off or over-throw the prevailing conditions in which we find ourselves thrown, even though we cannot overcome our conditionality, as being-thrown-projecting.

Marcuse (2005, 1928: 32) seems to concur with Flusser when he states that, “There is a Dasein whose thrownness consists precisely in the overcoming [over-throwing] of its thrownness.”

Thrownness, (official) personas and cognitive dissonance

Howes (2012) writes that a number of East German autobiographical texts written after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, such as Claudia Rusch’s (2003) Meine Freie Deutsche Jugend [My Free German Youth], explore the theme of cognitive dissonance, which draws out an element of thrownness, the awareness of finding oneself in a situation.

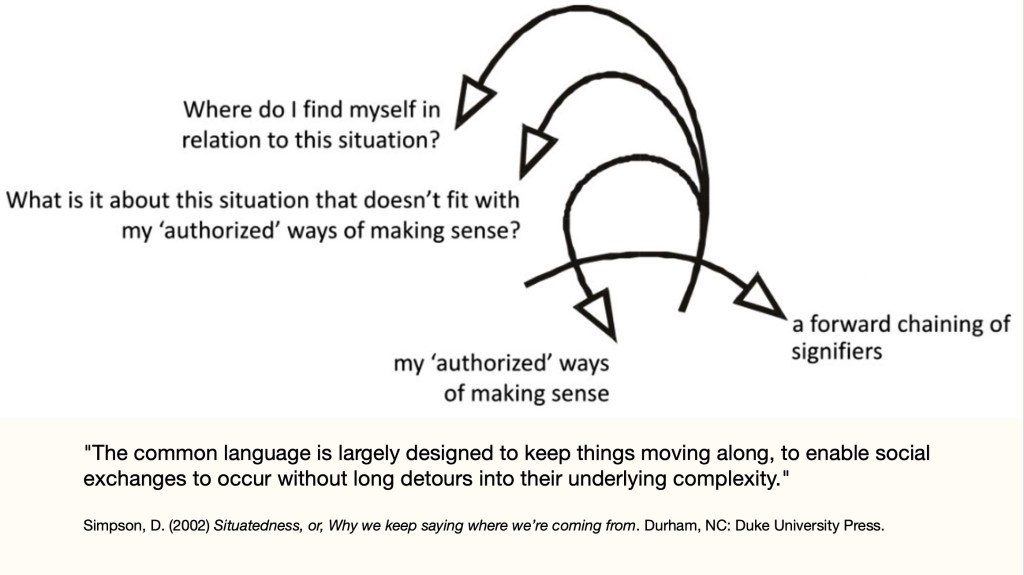

Lacan diagrams this situation in the following way:

In these texts, the narrating subject fails to recognise herself fully in the persona which the State and her family meant for her to assume, that is, into which she is presumed to have been thrown. This was the case even as she participated in, came to like and, indeed, even love the practices which articulated that persona. Such narrators are characterised by their disconnectedness from the institutions within which their lives are led, such as the schools, the Free German Youth (FDJ), the official youth movement of the German Democratic Republic and the Socialist Unity Party of Germany, the union and the family.

This narrative technique is one of disavowal; disavowal of a life to which she never really subscribed, leading to a splitting of the subject between the life she was supposed to lead, that into which she was thrown, and the life she actually led, her endeavour to over-throw that life, to design (un-throw) her own life.

The issue to be explored, in relation to design practices, is that one is given a persona, for example, a name, a story, a place of ‘origin’, before one can develop one’s own persona. That persona(l) development must begin not from scratch but from what one is given: the gift, the inheritance, the sitution. Persona(l) development is therefore development of a persona, based on a given persona, achieved through exosomatic choices, which are themselves framed by designing and design artefacts and constrained by the starting point, the given: that into which one is thrown and that which one ‘finds’. That ‘finding’, however, rather than simply being a matter of what is ‘presented’, the phenomena which one perceives as obvious, may become a process of discovery and indeed invention. Thrownness, givenness and foundness are, in one sense, one and the same. Nevertheless, their differences permit development, change, movement and motivation: the admitting of the other through the process of bricolage, the putting together in a novel fashion of that which comes to hand.

That into which one is thrown, that which is given and that which is found become affordances which only come into existence once one begins to recognises them as ‘circumstantial’, the accidents in which one is immersed and in whose development one is participating. One learns to act corporeally and one learns to speak semiotically and linuistically back-to-front, so to speak, by mimickry and ventriloquism of the self that one finds one has been given prior to the development of one’s self as self. Such mimesis is not an afterthought but a (be)forethought.

Notes

[1] As Joydeep Bagchee (2013) informs us, the concept of Entwurf, as projection, was central to Heidegger’s writings from 1927-1930. However, because for Heidegger Entwurf ceases to be a viable mode for thinking about or construing the finitude of human existence, it becomes progressively more marginalised and rare in Heidegger’s thought.

References

Aicher, O. (2015) Analogous and digital. Berlin, DE: Ernst and Sohn

Bagchee, J. (2013) The End of Entwurf and the beginning of Gelassenheit, Heidegger Circle Proceedings, 47, pp. 247–274. doi: 10.5840/heideggercircle20134713.

Hanke, M. (2016). Vilém Flusser’s philosophy of design: sketching the outlines and mapping the sources. Flusser Studies, 21 1–26. Available from http://www.flusserstudies.net/sites/www.flusserstudies.net/files/media/attachments/hanke-flusser-philosophy-design.pdf [Accessed 17 April 2018].

Heath, S. (1984) Ambiviolences: notes for reading Joyce, in Post-structuralist Joyce : Essays from the French. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 31–68.

Heidegger, M. (1962) Being and time. Translated by J. Macquarrie and E. Robinson. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Howes, W. S. (2012) Punk avant-gardes: disengagement and the end of East Germany. University of Michigan. Available at: https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/91534/howesws_1.pdf (Accessed: 8 April 2016).

Jenny, M (2025) Man and myth. Financial Times, 7 June, Life and Arts, p.7.

Marcuse, H. (2005, 1928) ‘Contributions to a phenomenology of historical materialism’, in Wolin, R. and Abromeit, J. (eds) Heideggerian Marxism. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, pp. 1–33.

Shafak, E. (2025) This much I know. Observer, 8 June, Magazine p.7

Sheehan, T. (2015) Making sense of Heidegger: a paradigm shift. London, UK: Rowman and Littlefield.

Shteyngart, G. (2022) ‘“The collapse of humanity is deathly funny”: Gary Shteyngart on writing comedy in difficult times’, Guardian, 15 January, Saturday pp.55-57. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/jan/15/the-collapse-of-humanity-is-deathly-funny-gary-shteyngart-on-writing-comedy-in-difficult-times (Accessed: 16 January 2022).