RELATED TERMS: Remembering: Mnemonics, Mnemotechne and Memory

[Katie] Hafner: I’ve heard Bran [Ferren] say before that he thinks technology should be invisible.

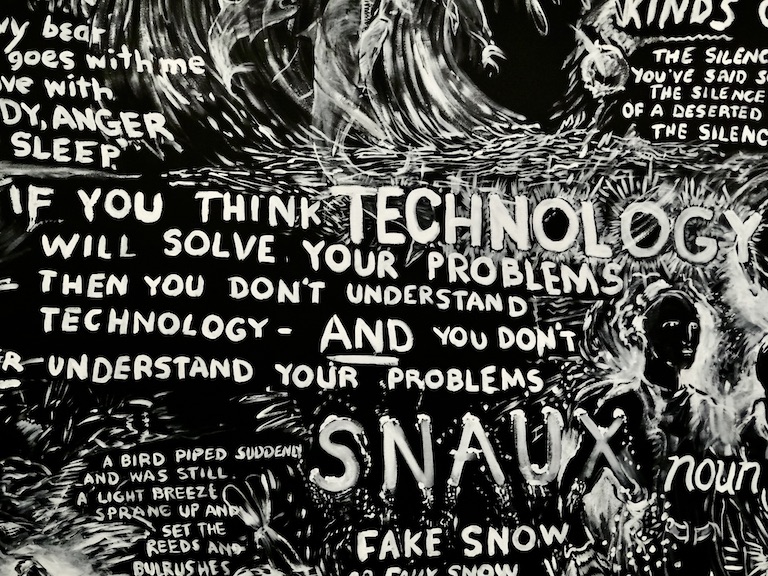

[Danny] Hillis: Good technology ceases to become technology. You don’t think of a pencil as technology, because it just does what it’s supposed to do. You don’t think of a book as technology, because it’s been refined enough that it becomes invisible. You probably don’t think of the telephone much. You still think about computers a lot, because they’re so bad.

[Marvin] Minsky: I have a slogan: when you confront something new you should try to understand it.

[Alan] Kay: I’ll give you a slogan: technology is all that stuff that wasn’t around when we were born, because the stuff that was around when you were born was just part of the landscape. Like the pencil.

[Bran] Ferren: I think of technology as just being one of the byproducts of human imagination.

[Danny] Hillis: I think technology is all the stuff that doesn’t work yet.

[Alan] Kay: I think it’s all the stuff people [have] gotten used to. At a lecture there was an anti-technologist up on the stage, and I said, “Let me come up on the stage and relieve you of all the technology you have on you,” and I took off his watch and started taking off his clothes, and at some point this guy realized he was surrounded by technology. (Hafner et al. 1997)

In the context of the design of narrative environments, technologies are understood to be interconnected systems, media or frames. At any one time, there is an accumulation or ecology of systems-media-frames. Over time, within such ecologies, certain systemic media frames achieve dominance, while previously dominant systems become subordinate. They do not simply disappear, however.

Within these systemic media frames, individual technical artefacts act as a form of memory that constitutes the fabric of human historicity and sociality. They do so by providing the ground of that which is always already there for human beings or, in other words, that into which one has been thrown. In that sense, following Stiegler (1998), they are a kind of tertiary memory, a particular kind of mnemotechne that differs from secondary memory, such as writing and oral topical techniques (method of loci or method of topoi), as well as the primary memory of human recall as mnemne.

In another, related vocabulary, such systemic media frames might be said to constitute the (always already there) deictic centre or ground which orients relationships, as points of reference, to other people (subjects, subjectivity, intersubjectivity, subjecthood), things (objects, objectivity, objectification and corporeitisation), spatiality and temporality and sets the contextual horizons establishing relevant place.

Technicisation is, therefore, not what produces loss or a weakening of memory, a hypomnêsis, as is argued in Plato’s Phaedrus, but rather a different kind of remembering.

Stiegler (2009: 1-2) states that,

“The Fault of Epimetheus was my attempt to show that this disorientation is originary, that humanity’s history is that of technics as a process of exteriorization in which technical evolution is dominated by tendencies that societies must perpetually negotiate. The “technical system” is constantly evolving and rendering the “other systems” that structure social cohesion null and void. Becoming technical is originarily a derivation: socio-genesis recapitulates techno genesis. Techno-genesis is structurally prior to socio-genesis — technics is invention, and invention is innovation — and the adjustment between technical evolution and social tradition always encounters moments of resistance, since technical change, to a greater or lesser extent, disrupts the familiar reference points of which all culture consists.”

Postscript

In a similar vein to the sentiments expressed at the top of this post, Adam Rutherford (2019: 19) writes that the science-fiction writer Douglas Adams came up with three rules concerning our interaction with technology, but they may just as easily be applied to designs and designing. Thus, we might say,

- 1. Anything (any designed entity) that is in the world when you’re born is normal and ordinary and is just a natural part of the way the world works.

- 2. Anything (any designed entity) that’s invented between when you’re fifteen and thirty-five is new and exciting and revolutionary and you can probably get a career in it.

- 3. Anything (any designed entity) invented after you’re thirty-five is against the natural order of things.

References

Hafner, K. et al. (1997) Disney’s Wizards, Newsweek. Available at: https://www.newsweek.com/disneys-wizards-172346 (Accessed: 29 January 2024).

Rutherford, A. (2019) Humanimal: How homo sapiens became nature’s most paradoxical creature. New York, NY: The Experiment.

Stiegler, B. (1998) Technics and Time 1: the fault of Epimetheus. Translated by R. Beardsworth and G. Collins. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Stiegler, B. (2009) Technics and time 2: disorientation. Translated by S. Barker. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.