RELATED TERMS: Actant; Happenings; Metalepsis; Methodology and Method; Paradigm; Performance Art;

“You are more than entitled to know what the word ‘performative’ means. It is a new word and an ugly word, and perhaps it does not mean anything very much. But at any rate there is one thing in its favour, it is not a profound word. I remember once when I had been talking on this subject that somebody afterwards said: ‘You know, I haven’t the least idea what he means, unless it could be that he simply means what he says’.”

Austin, J. L. (1970). Philosophical papers. 2nd ed.. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

“The last two decades or so have seen a small paradigm shift throughout the arts and humanities. Where, not so long ago, everything was regarded as ‘text’ or ‘discourse’, scholars are now more likely to talk about ‘performance’ and ‘the performative’ and ‘the body’ or ‘the bodily’. It is easy to be cynical about fashionable jargon, but, when cogently employed, the nomenclature does suggest, if not a revolution, then a significant shift in emphasis.”

Heile, B. (2006). Recent approaches to experimental music theatre and contemporary opera, Music & Letters, 87 (1), pp.72-81.

Gregson and Rose (2000) distinguish performance and performativity in the following way:

“…our argument is that performance – what individual subjects do, say, ‘act-out’ – and performativity – the citational practices which reproduce and/or subvert discourse and which enable and discipline subjects and their performances – are intrinsically connected, through the saturation of performers with power.”

From the perspective of design practices, Gregson and Rose (2000) indicate that their argument needs to be extended to space:

“Space too needs to be thought of as brought into being through performances and as a performative articulation of power.”

Finally, they emphasise the importance of recognising, “the complexity and uncertainty of performances and performed spaces”.

The relevance of the notions of performative and performativity, alongside that of performance, to the design of narrative environments is that narrative environments are performed or enacted. In being enacted, they constitute a field of actantiality or performativity in which different levels of narrative, different levels of existence and different modes of existence are intertwined, forming a tangled hierarchy in which specific diegetic or ontological metalepses (transgressions from one level of narrative to another or from a narrative modality of existence to a more everyday mode of existence) may be realised. In these ways, the interweaving of the material and the immaterial aspects of cultural practices can be explored as well as the inter-relationships between the actual (the ‘is’) and the potential (the ‘as if’).

Chris Salter (2010: xxi) writes that,

“Performance as practice, method, and worldview is becoming one of the major paradigms of the twenty-first century, not only in the arts but also the sciences. As euphoria for the simulated and the virtual that marked the end of the twentieth century subsides, suddenly everyone from new media artists to architects, physicists, ethnographers, archaeologists, and interaction designers are speaking of embodiment, situatedness, presence, and materiality. In short, everything has become performative.”

In design practices, performative typically applies to the behaviour that is evoked in participants when they, through engagement with designs and/or design contexts, express themselves ‘unconsciously’, as part of a system or network of performativity or actantiality, rather than ‘consciously’ and deliberately, as ‘users’, which is more in the realm of scripted or improvised (unscripted), but framed, performance.

A performative utterance is one which does what it says. For example, if a person says “I promise to be there”, in normal circumstances this constitutes a promise to be at the specified place at the specified time, i.e. implies a course of action to fulfil the promise. The concept was originated by J. L. Austin, who contrasted performatives with constatives. Constatives make statements about the world which are either true or false. Performatives are neither true nor false (although whether the person making the promise turns up at the specified time and place will determine whether a promise was actually made or a deceit uttered).

The difficulties, and indeed the more interesting questions, arise when it is realised, as Austin did, that any utterance may be performative and that a clear and permanent distinction between performative and constative is hard to maintain. More depends on the circumstances of the utterance than the form of the utterance, although both have significance, e.g. barking out an order (Halt!) does much to constitute its status as ‘a command’ to act in a specified way.

Matters get even more interesting when the notion of “in normal circumstances” is opened to question (what are they?) and the question of whether the person uttering the performative fully intends to do what they say they will do, for example, whether they really intend to be there at the specified place at the specified time when they say “I promise to be there” (as noted above, concerning whether a promise was actually made, or some other act performed, such as a deception). The utterer may be lying, joking or may have forgotten a previous arrangement that they have made in which they promised to be somewhere else, i.e. intentionally or unintentionally invalidating the performative act. Alternatively, they may be uttering the sentence in the context of acting in a play.

In short, circumstances are the important factor, and their ‘normality’ should not simply be assumed but carefully considered.

The Performative: From the 1950s to the 21st Century

For a survey of the pathways along which the notion of the performative has travelled, see Jeffrey Nealon’s (2021) Fates of the Performative. Nealon traces it from J. L. Austin’s ordinary language philosophy of the 1950s, through its becoming

a linchpin for deconstruction in Derrida’s philosophy and associated American deconstructive literary theorists, to its value in thinking about resistant identities in the feminism and queer theory of the 1980s and 1990s, for example, in the work of Judith Butler and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick. It subsequently became important as a concept in ethnic studies and its overlaps with performance studies, such as in the work of José Estaban Muñoz, Fred Moten and Diana Taylor. Furthermore, it became key to understanding the ‘agency’ or ‘actantiality’ not just subjects and identities but also of objects, for example, in Bruno Latour’s actor-network theory and Jane Bennett’s concept of vibrant matter. Eventually, Karen Barad applied it to matter itself. Thus, for Barad (2007: 152) in Meeting the Universe Halfway, “All bodies, not merely ‘human’ bodies, come to matter through the world’s iterative intra-activity — its performativity.”

The illocutionary, the performative and collective assemblages of enunciation: Order words and social obligation

In A Thousand Plateaus, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari make the distinction between the performative, as that which one does by saying it, for example, I swear by saying “I swear”, and the illocutionary, as that which one does in speaking, for example, I ask a question by saying “Is…?”, I make a promise by saying “I promise” and I give a command by using the imperative, and so on. In this way, they make the performative sphere (doing by saying) part of a larger illocutionary sphere (what one does in saying). Thus, they argue,

“The performative itself is explained by the illocutionary, not the opposite. It is the illocutionary that constitutes the nondiscursive or implicit presuppositions. And the illocutionary is in turn explained by collective assemblages of enunciation, by juridical acts or equivalents of juridical acts, which, far from depending on subjectification proceedings or assignations of subjects in language, in fact determine their distribution… these “statements-acts” assemblages…in each language delimit the role and range of subjective morphemes.” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1988: 78).

They call these illocutionary acts, these “statements-acts” assemblages, “order-words”. They continue,

“Order-words do not concern commands only, but every act that is linked to statements by a “social obligation”. Every statement displays this link, directly or indirectly. Questions, promises, are order-words. The only possible definition of language is the set of all order-words, implicit presuppositions, or speech acts current in a language at a given moment.” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1988: 79)

For Deleuze and Guattari, the relation between the statement and the act is internal or immanent. It is not one of identity, however, but of redundancy. Given this,

“Language is neither informational nor communicational. It is…the transmission of order-words, either from one statement to another or within each statement, insofar as each statement accomplishes an act and the act is acomplished in the statement.” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1988: 79)

In this way, the collective assemblage of enunciation is the redundant complex of the act and the statement that necessarily accomplishes it. These acts, in turn, are the set of all incorporeal transformations in a given society, and these incorporeal transformations are attributed to the bodies of that society.

Performance Theory – Schechter

The terms performance and performative are important for designs because, it is argued, they are performed by a participant. This performance takes on a different character depending on the design itself and may involve a combination of consumption by a consumer; reception by a reader, spectator or audience; or instrumental use by a user, as well as scripted or unscripted (improvisational) actions and decisions by the participant.

The performativity of ta design may also be discussed in terms of actantiality or actantiality-passantiality. In any case, through performance, the ‘as if’ is brought together with the ‘is’, to explore actual or potential transformations from one state of being to another. Systems of performative transformations, whatever their material aspects, Schechner (2004, xviii) notes, “also include incomplete, unbalanced transformations of time and space: doing a specific “there and then” in this particular “here and now” in such a way that all four dimensions are kept in play.”

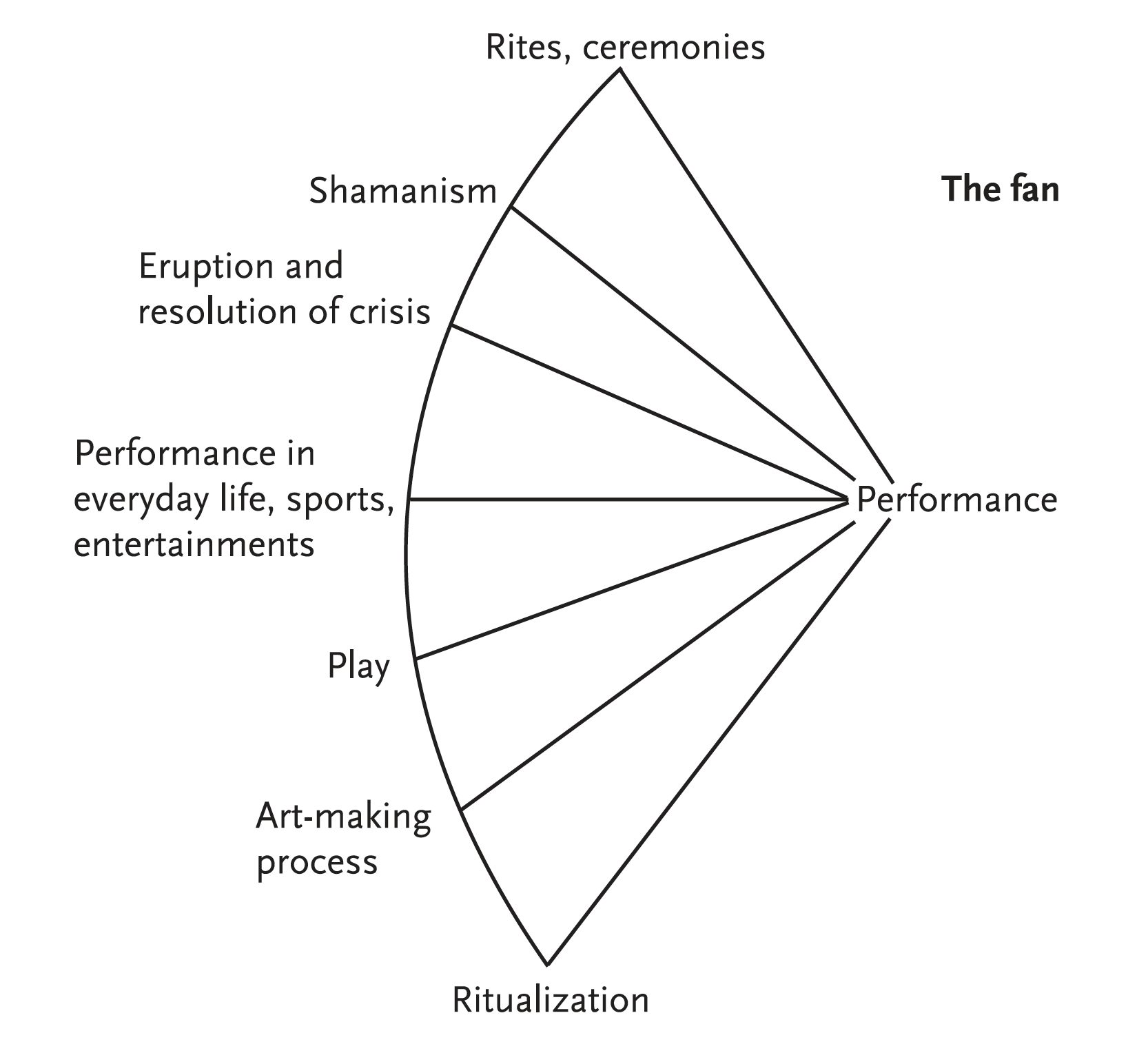

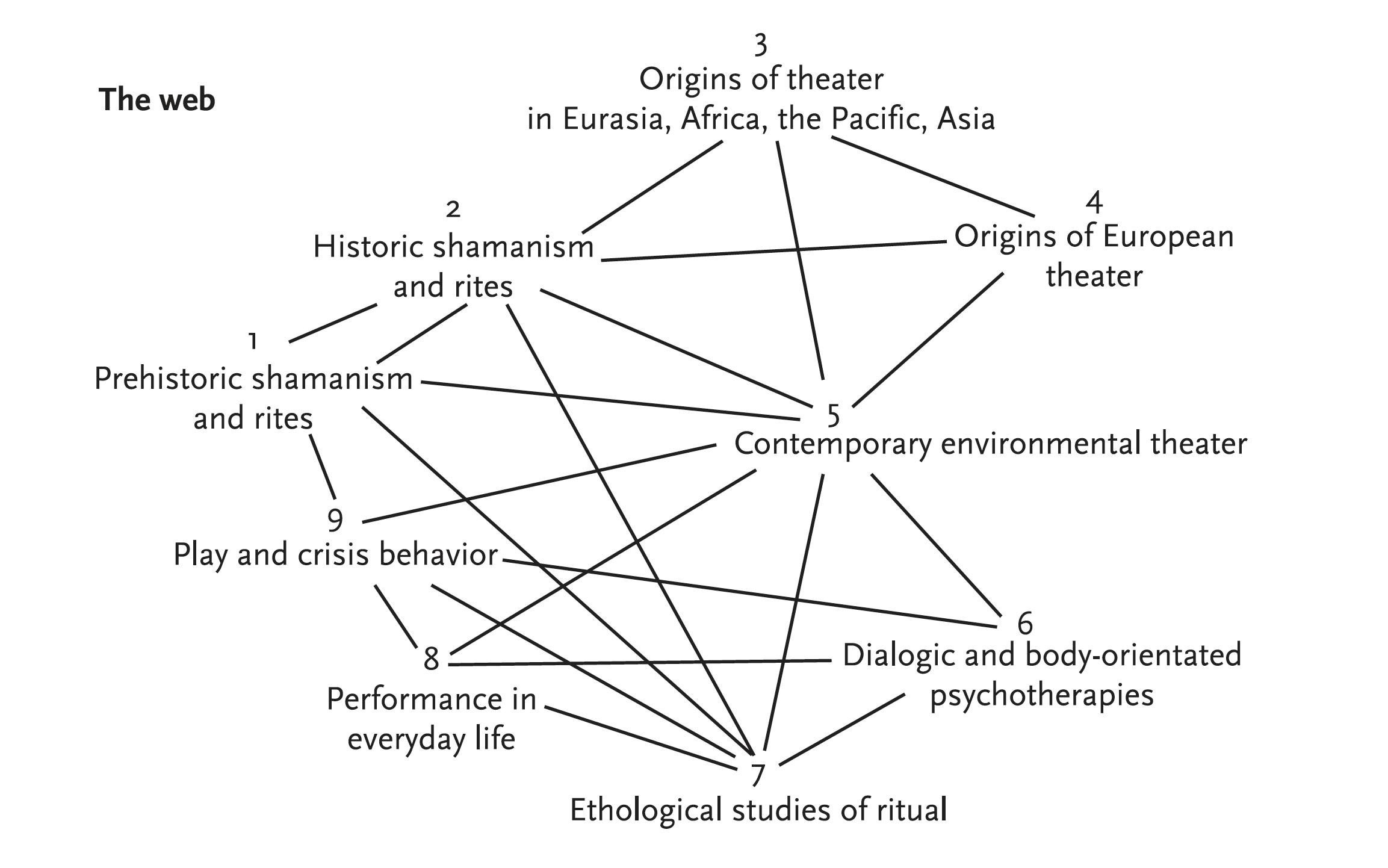

Richard Schechner conceives of the topics which relate to the term performance as a fan or as a web, as follows:

Source: Richard Schechner, Performance Theory

Source: Richard Schechner, Performance Theory

Source: Richard Schechner, Performance Theory

Source: Richard Schechner, Performance Theory

References

Austin, J. L. (1970) Performative utterances, in Philosophical papers. 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Barad,K. (2007) Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Gregson, N. and Rose, G. (2000) Taking Butler elsewhere: performativities, spatialities and subjectivities. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 18, pp. 433-452.

Nealon, J. T. (2021) Fates of the performative: From the linguistic turn to the new materialism. Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota University Press.

Parker, A. and Sedgwick, E. K. (eds) (1995) Performativity and performance. New York, NY: Routledge.

Salter, C. (2010). Introduction. In: Entangled: technology and the transformation of performance. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, xxi–xxxix.

Schechner, R. (2004) Performance theory. Rev & exp.ed. New York, NY: Routledge.